Trimingham

Arden was one of America’s largest homes when E.H. Harriman completed his 100,000 square foot mansion in Tuxedo Park at the turn of the last century. Forty miles north of New York City, Arden had nearly 100 rooms on 40,000 acres of land. Harriman had purchased the property from the Parrott brothers, who supplied the Union Army with cannons and the well-known Parrott Rifle during the Civil War.

Never one to enjoy school, Harriman left at 14 to pursue a career on Wall Street, fortuitously just as the Civil War was unleashing a new speculative fervor in America’s financial institutions. He proved to be so adept at combing through financial statements of railroads and picking winners from losers in the turbo-charged stock market, at the age of 21, he owned a seat on the New York Stock Exchange. Harriman’s early railroad investments led to a profitable association with Stuyvesant Fish, a Wall Street railroad stock speculator (Fish and Harriman became estranged some years later when Fish’s wife, Mamie, snubbed Harriman’s wife, Mary, at a tea party at Crossroad, their Colonial Revival home in Newport, RI, where Mrs. Fish’s Harvest Festival Ball in August signaled the end of the Newport social season).

The Harriman myth revolved around his seemingly magical ability to transform rusting, decrepit railroads into modern moneymakers. His most ambitious project was rescuing the failing Union Pacific railroad system in 1897. A key part of his recovery plan was changing the management culture at the railroad by decentralizing the organization. Adroitly using his Wall Street relationships, he restructured its heavy debt and rebalanced the capital structure. He personally examined every mile of the huge railway system, meticulously noting where critical capital expenditures were needed on every railway crossing, dispatch station and signal light. One reason for Harriman’s success as a railroad manager was his innovative directive to streamline operations and standardize the company’s fleet of railroad cars.

He recognized that America’s railroad system was rapidly becoming over-built, due to the abundant liquidity provided to the railroad industry by Wall Street and London financiers. Success would depend on attention to detail and prudent financial plans. Ultimately, Harriman succeeded not so much because he was an original thinker, but because he implemented his financial strategy on a grand scale, which other railroaders shied away from. As a financier who witnessed the boom and bust of America’s economy after the Civil War, he knew when to open the money spigot — and when to close the valve.

Fast forward 100 years. Once more, the markets are turbo-charged and flush with liquidity. Equity markets are near record highs. Property prices in key global cities are at record multiples of inhabitants’ earnings. Private equity groups have never had it so good, raising record amounts of liquidity at the fastest pace in a decade. The recent uptick in highly leveraged mega deals comes as global M&A for the first nine months of 2018 eclipsed the high-water mark of 2007.

A Shift to the Shadow Banks

Ultra-loose monetary policy and quantitative easing have repaired bank balance sheets. Since the financial crisis, many bank ABL and leveraged finance groups moved into high gear. But tightened bank oversight has shifted risk, notably to the shadow banking sector. This trend should accelerate in 2019.

Asset managers, hedge funds and insurance companies, hungry for yield, now carry the kinds of risk that used to be the preserve of banks.

New credit funds, BDCs and asset-based lending companies are announced almost weekly. PE funds are setting up their own credit arms, partly to reduce costs on their own transactions and partly to do third-party deals. KKR, Bain and Carlyle — to name a few — have massive amounts of capital to deploy. This feeds the competitive environment.

But such a large volume of funds brings its own pressures. Many new credit funds only get paid when they deploy funds, so the challenges to book deals are intense. Some non-bank lenders are responding to this pressure by overlooking the elastic and creative mathematics behind many investment bankers’ EBITDA calculations. This, in turn, has led to a string of deals with some nose-bleed valuations and debt levels that were seen just before the financial crisis.

Three of the four biggest U.S. private equity firms now manage more money in credit funds than in their private equity arms, a marked turnaround from a decade ago, when private credit funds accounted for about 20% of assets. All told, private credit funds have amassed $160 billion in dry powder, twice what they had a decade ago and enough to support up to $400 billion in business lending once leverage is added.

As an example of the shift from bank lenders to non-bank lenders, HSS Hire in the UK recently closed on a new term loan facility of £220 million ($290.17 million) provided by HPS Investment Partners and a revolving credit facility of £25 million ($32.97 million) provided by HSBC and Natwest. Historically, HSS had mostly used bank borrowings to finance its operations. HSS had a pre-tax loss of £85.2 million ($112.4 million) in 2017 and a £17.4 million ($23 million) loss in 2016. In the past decade, HPS has emerged as a major force in asset-based lending.

The explosive growth of credit funds is reflected in rising leverage ratios, sometimes north of seven times EBITDA. A blockbuster deal with a Blackstone-led investor group to finance its 55% stake in Refinitiv, the Thomson Reuters data business, underscores market competitiveness. Leverage in the deal may exceed eight times EBITDA after EBITDA adjustments. High leverage isn’t the only ground-breaking aspect of this deal. According to Covenant Review, under the proposed terms of its bonds, the company can pay dividends to its owners even if it drastically underperforms — even to the point of financial distress. This deal is the fourth-largest since the financial crisis, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

The street views Refinitiv’s deal as a test for how much leverage companies with poor credit ratings can issue in the current market and how aggressively they can set the covenants in the face of aggressive assumptions about operating synergies. Robust or real-time covenants were attached to fewer than 30% of the leveraged loans written in the U.S. last year, according to the IMF. McKinsey estimates more than 6% of U.S. corporate bonds have been issued by companies which need to spend two-thirds of EBITDA.

Today, almost two-thirds of leveraged loan issuers are rated B2 or lower by Moody’s — less than half of the 2006 rate. Some of these transactions, many of which are heavily weighted in the borrower’s favor, will come back to haunt the credit funds. And banks are lending to BDCs and credit funds, which increases the leverage in the system. As an example of the liquidity offered to the marketplace by asset managers, Waterfall Asset Management recently launched its Specialty Commercial Finance Group to provide high-yield senior secured debt to specialty commercial finance companies.

PE players are increasingly looking at acquisitions of public companies as the buyout deal competition intensifies. According to Bain, the number of public-to-private deals doubled from 2016 to 2017. Looking ahead, 2019 will see a surge in mega-deals of $5 billion or more, according to The Financial Times. However, some of these deals will be challengingly expensive as PE funds compete against strategic buyers who are flush with liquidity from the tax change. With sky-high valuations, some PE players will need to find a diamond in the rough or break the company into pieces to justify the price.

Many of the ABL and cashflow deals will be done to support secondary deals where the company is sold by one PE player to another. The industry has done a record 576 secondary deals in 2018, according to Preqin. That compares with 394 similar transactions in the peak of the deal boom in 2007.

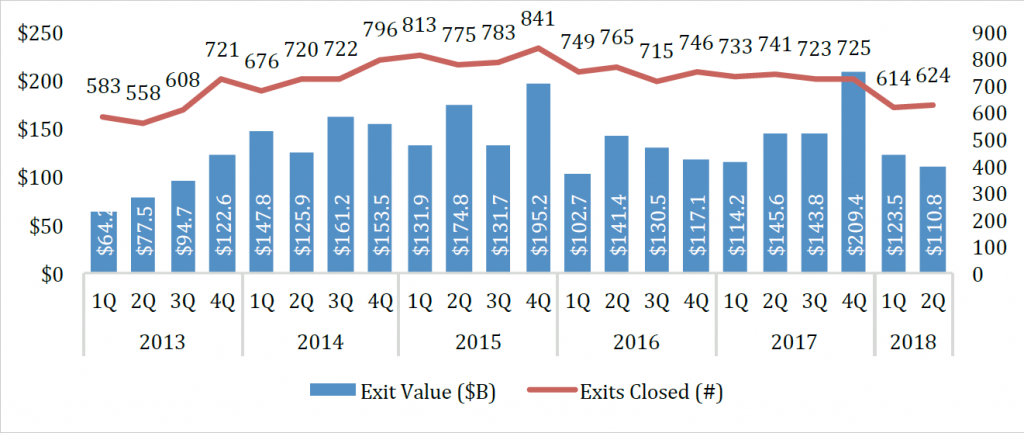

Pitchbook’s chart (see below) shows the increase in deal size (and valuations) from Q1/13 to Q2/18.

The issue with secondary deals is with dividend recaps, leverage, operating synergies and aggressive organic growth assumptions, which often end up disappointing. As an example, Simmons Bedding, which was bought and sold by private equity owners seven times over two decades, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 2009.

A Street Knife Fight While Wearing Tuxedos

The prominence of non-bank lenders is also coloring the bankruptcy process.

The street was caught by surprise recently by the decision of Toys “R” Us’ lenders to cancel the company’s brand name and intellectual property auction in bankruptcy court and instead revive the brand. The lenders plan to open a new company, including retail stores, under the Toys “R” Us and Babies “R” Us brand names using existing global licenses. Control of the fulcrum securities has pitted the lender group, including Solus Alternative Asset Management and other hedge funds, against Toys “R” Us’ foreign-subsidiary bondholders. Another knife fight may be brewing in the courts. This underscores the activist lenders who play today in the leveraged lending marketplace.

A similar scenario is playing out in The Gibson Guitar bankruptcy in Delaware. The legendary company made instruments for Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix and The Who, but with a changing demographic and the huge growth in computer-based electronic music and video games, Gibson increasingly has found itself out of tune with the marketplace.

Echoing Jimi Hendrix setting fire to his guitar and The Who smashing their guitars at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, Chapter 11 has created some serious damage to Gibson’s plan to reinvent itself by selling self-tuning guitars. Like a battle of the bands, the Delaware courtroom is a loud, pitched battle between Blackstone and KKR, two of the biggest secured lenders in the capital structure. Many asset-based lenders will be interested in the Gibson brand’s value in the Chapter 11 exit plan given the Toys “R” Us plan of reorganization. Gibson may be the first of many PE deals to pay a visit to The First State in 2019 and 2020.

Where is the Market Headed?

This intense competitive marketplace is reflected in the sluggish growth in commercial and industrial loans for the big U.S. regional banks. According to The Wall Street Journal, weak loan growth for these banks has been one of the mysteries of the economic recovery in the past two years. Through Q2/18, loan growth topped out at just over 5%, well below the double-digit increases seen a few years ago. Some regional banks are facing intense competition from community banks. The jaws of some workout bankers at regional banks are dropping as community banks rush to take them out of deals that barely have a pulse.

As a result of this liquidity, the boundaries of adjusted EBITDA are being pushed farther. Lenders are taking more liberal views of this with sponsors on deals with weaker core EBITDA. Some borrowers are straining to meet the EBITDA targets now. What happens when the economy weakens? One important macro risk credit committees are evaluating is the impact of the brewing trade war.

David Fiegel, president of Blackbird Asset Services in Buffalo, says, “The impact of current U.S. trade posturing is making a lot of our clients nervous. We have clients that have had orders grind to a halt as various players in their respective supply chain(s) await the next moves on the international chess board. The stakes can be huge, and it seems that everyone’s crystal ball is cloudy.” Fiegel notes current policy uncertainty can place some tariff/trade-sensitive borrowers at a higher risk of default. “Until the crystal ball clears, it’s a little like the Wild West in some markets,” he says. The trade issue has weighed particularly hard on share prices of industrials and materials companies, which account for the more than 20% of the 80 stocks in the S&P 500 that have tumbled at least 20% from their 52-week highs, the common definition of a bear market.

Darren Latimer, co-founder and CEO of Stonegate Capital in Chicago, says, “The health of our portfolio is stable as of now, and we haven’t seen material revenue or margin deterioration in our portfolio companies, but the system seems very vulnerable to shock waves and those are too random to predict.”

Michael Sharkey, president, MB Business Capital, adds, “The silver lining in this market and the reason that we continue to set records within our group financially is that for now, our borrowers are enjoying an unprecedented growth market, resulting in the need to increase usage under their lines of credit and grow capacity through capital spending and by making add-on acquisitions. That organic growth is resulting in increased utilization and requests for additional credit.”

“Stonegate continues to build our portfolio focused on 1) high-growth consumer products/food and beverage brands, 2) software companies and 3) traditional asset-based borrowers,” says Latimer. “Because we cannot completely handicap the economy, government interference or other global events, we are being more cautious on companies who rely on tariff-based inputs (steel/auto), commodities (oil) and distressed situations.”

Looking ahead to 2019, Lori Potter, managing director of Originations, from Great Rock Capital, says, “No one can fully predict what the market appetite will be for 2019, but as a non-bank ABL lender, we recognize that viable businesses can experience stress during any phase of an economic cycle. Great Rock will continuously lend throughout the cycle, but, particularly in a period of economic stress, our ability to structure creative financial solutions will provide companies with liquidity options they are not likely to find from traditional lenders.”

What Inning Are We In?

An important question lenders are continually asking one another in plotting the course for the next year is “what point are we at in the business cycle? Are we in the eighth inning of a nine-inning game? Or a 15-inning game?”

“Financially, we are having our best year ever,” Sharkey says. “Having said that, competition within the ABL world is at an all-time high. In my 40 years of lending, I have never seen a market so flush with liquidity. Looking at the better-quality deals, the lines between ABL, cash flow and traditional bank lending have blurred completely. On the tougher deals, new non-bank owned finance companies have captured the market with fully margined ABL deals that are so aggressive that pricing isn’t even a factor that the borrowers are considering. In short, loose and aggressive structures with minimal reporting are ruling the day on the better deals while we can no longer win the tougher deals with a conservative structure and reasonable pricing.”

Fiegel remains more cautious. “Take the scrap metal market as a proxy for the economic and credit impact of the trade war. The scrap markets are suffering steep declines as businesses inside countries impacted by the first round of tariffs have hit the scrap metal market negatively. Some speculate this negative price pressure is, in effect, an attempt to recoup money lost to tariff increases levied by the U.S.”

Industry veterans will all agree that deals done in the 12- to 18-month period before a recession are often the most difficult to collect. Many seasoned ABL players are proceeding cautiously when it comes to deal structure. While they have been rare in recent years, the supersized buyouts inevitably stir bad memories of the years immediately preceding the financial crisis, when there was a flurry of covenant-lite deals quickly followed by Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

The 2019 ABL Outlook in Europe

Across the pond, “CFA Europe is going from strength to strength,” reports Jeremy Harrison, group regional head and senior vice president, Bank of America Business Capital EMEA. “The chapter continues to attract new credit funds and other important non-bank lenders such as Chiron Financial. We have Apollo and TPG on our Steering Committee, which reflects the increasing profile of the association. We are broadening our reach further into Europe with successful events in Brussels and Paris in 2018 and plans for Amsterdam and Munich in the coming year.”

However, “uncertainty prevails. Brexit is dampening market enthusiasm,” he adds. “Many of the members of our CFA Chapter in Europe say it is difficult to predict how 2019 will look. There is a general expectation that 2019 will see a greater degree of market caution. Up to Q2/18, borrowers could get great terms. Now, credit committees are getting pickier about EBITDA adjustments.”

According to Kon Asimacopoulos, partner, European Restructuring, Kirkland & Ellis in London: “The UK government has issued guidance on the prospect of a ‘no deal’ Brexit, including the possible future of the cross-border European restructuring and insolvency landscape. A ‘no deal’ Brexit would negatively impact the UK’s restructuring and insolvency framework, the force of which depends, in part, on its pan-European reach. The ability to deal with insolvencies via a single process, with automatic recognition across the E.U., would make it more complex, lengthy and expensive to resolve cross-border mandates, with the prospect of parallel proceedings.” Partha Kar, partner at Kirkland & Ellis in London, adds a sobering thought: “This would jeopardize the prospect of rescue, and reduce returns for stakeholders — and undermine the UK’s status as a leading global restructuring hub.”

Leverage & Recoveries Play Out in the Next Recession

As a result of the competition posed by nonbank lenders, recoveries in the $1.4 trillion market for non-investment grade loans will be lower because companies have fewer covenant restrictions on excessive dividends and stripping corporate assets. Indeed, one mid-Atlantic banker commented that banks have no business doing dividend recap loans for sponsor companies at this stage of the credit cycle. Moody’s Investor Service is predicting that the typical recovery on leveraged loans will be 61% of face value in the next recession, compared with the 77% historical average. Recoveries on second lien loans is predicted to be 14% from about 43% in the previous recession. This means unsecured creditors will also face worse recoveries, with Moody’s predicting 32% recoveries in the next default cycle compared with the historical average of 40%.

In an April 2018 report warning about lower recoveries on both junk bonds and loans, Guggenheim Partners told clients that, unlike the last recession, which was triggered by unsustainable levels of household debt, the next recession will be traced back to the corporate debt market. And Moody’s says the next default cycle will include a wider swath of industries because the market has exploded from $800 billion in 2008 to $1.4 trillion in 2018. In the event of a liquidity contraction in the economy, the sheer size of this leverage in the economy will amplify the lowering of the tides.

What’s a Prudent Lender to Do in 2019?

With these conflicting signals from the lending marketplace, what’s a prudent ABL lender to do in 2019? Dan Karas, executive vice president, chief lending officer, TBK Bank in Dallas sums up the sentiment of many asset-based lenders: “With respect to 2019, I’m reminded of the line from Frank Sinatra’s song, New York, New York, where he sings, ‘if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere.’ The corollary is that with strong economic fundamentals in 2018 that appear to be sustainable in 2019, ABL clients should be able to generate strong performance. However, if they can’t make it in the current environment, then they aren’t likely to survive. Overall, I’m optimistic about 2019.”

Sharkey adds, “I wouldn’t say that we are reefing down our sails — however, the winds are not cooperating right now. We are sticking to tried and true logic and pricing, and doing deals that our long-term relationships and key partners entrust us with. There will be busted plays on both ends of the risk spectrum in the not-so-distant future, and, at that point, we should be relatively trouble-free with the appetite and ability to restructure transactions and pick up the pieces.”

Most recessions are short and shallow, 12 months on average. Economist Martin Feldstein, advisor to President Reagan and a member of the Wall Street Journal’s board of contributors, sees the next recession differently. He thinks the Fed will not have the headroom to cut rates, since the fed-funds rate is expected to rise to only 3% over the next two years. There also won’t be much room for major fiscal intervention. The $1 trillion annual deficit in the coming years won’t allow recession-fighting spending, since federal debt is predicted to rise from 75% of GDP to nearly 100% by the decade’s end. Consequently, he thinks the next recession may last two to three years.

All this to say that some sectors of the economy, which are highly leveraged and vulnerable to an extended trade war, now are flashing yellow, and many lenders are taking heed. As the U.S. enters its 10th year of economic expansion, some ABL players are testing their brakes…just to make sure. While some credit funds and PE players will continue to widen the guardrails on the road ahead, prudent lenders are taking stock of the situation. No one wants to go over the edge of the cliff with the accelerator to the floor, leaving no tire skid marks.

At the turn of the 20th century, Harriman was as well-known as J.P. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie and other captains of American industry during its most prosperous, gilded age. Banking, railroads, the stock market, oil and steel were the major paths to great wealth from the end of the Civil War until the Great Depression. Morgan stood for banking, Rockefeller for oil, Carnegie for iron and steel and Harriman for railroads. One skill that all of these industry giants possessed was a clear idea of the path ahead, with its risks and opportunities. Harriman’s legacy continued through the 20th century with his son, Averell, who became Secretary of Commerce under President Truman and later, Governor of New York State.