Managing Partner

Pemberton

For more than a decade following the Global Financial Crisis, the U.S. economic recovery was sustained by ultra-loose monetary policy characterized by near-zero interest rates and Federal Reserve asset purchases that boosted its balance sheet to a then record $4 trillion.

With a marginal buyer, 10-year U.S. Treasury yields steadily declined from 3.8% at the end of the crisis to 1.8% by the end of 2019, so that, even as the U.S. stock market enjoyed the longest bull run in history, quantitative easing left institutional investors wondering how they could meet long-term funding obligations without taking on more risk than their mandates permitted.

“This could be a low rate environment for a period of time and we have to factor that in when we do our allocation work,” Marcie Frost told Bloomberg in July 2016, shortly after being appointed CEO of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), the world’s largest public pension system, which currently has more than $400 billion in assets.

But now, as they gather over Zoom for after-market happy hour martinis on a Friday, allocators at public pensions, Taft-Hartley retirement plans for union workers and insurance companies across the U.S. could be forgiven for giddily reminiscing about the halcyon days when treasuries offered such “respectable” yields.

Massive additional Fed stimulus to combat the COVID-19 pandemic’s economic impact, which expanded the Fed’s balance sheet to $7 trillion, has left 10- and 30-year U.S. Treasury yields at about 0.7% and 1.5%, respectively. And that’s before you factor in inflation — the US sold $12 billion of 10-year treasury inflation-protected securities in mid-September with a real yield to maturity of -0.966%.

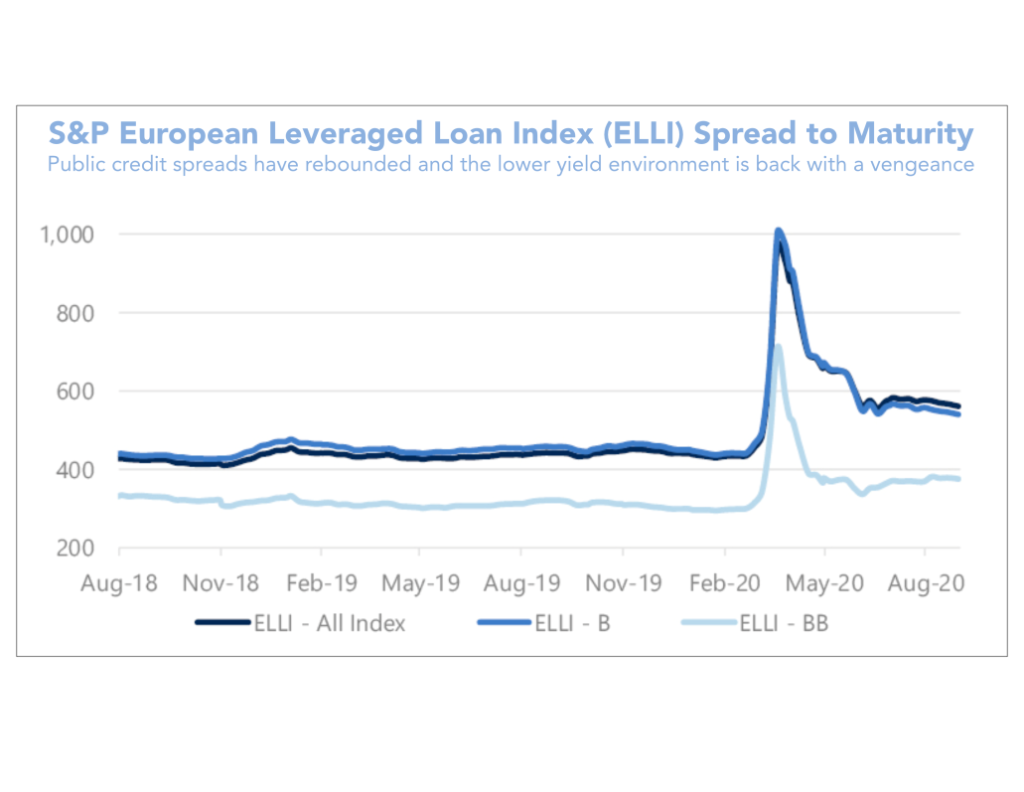

Just as significantly, In March, when the Fed extended stimulus for the first time to investment grade bonds, asset-backed securities and commercial paper, the trajectory of corporate bond markets immediately switched, with top-rated debt now offering a 10-year yield of about 1.8%.

The party soon spread to junk issuance, with about 40% of deals sold in the first week of August priced at a yield of less than 4%. Most notably, in August, aluminum packaging company Ball Corp. borrowed $1.3 billion for 10 years at a yield of 2.875%, a record for a bond rated below investment grade with a maturity of more than five years.

And it’s no temporary blip. Treasuries will likely continue to earn virtually nothing in real terms for years after Fed Chairman Jerome Powell effectively ruled out rate hikes through at least 2023, which also means investment grade and high yield corporate bonds will probably provide ever-diminishing returns.

The unprecedented Fed stimulus also helped the S&P 500 to surge 60% to a record on Sept. 2 from its March 23 low. But the benchmark’s 4% slide in September and bounce back in early October suggest jitters about the resilience of the U.S. consumer — upon which 70% of GDP depends — as Congress drags its feet on renewing expiring fiscal stimulus programs amid uncertainty about the direction of corporate taxes and regulation following the presidential and Senate elections.All of which leaves U.S. public pensions, with assets of about $4.65 trillion, and other institutional investors looking increasingly to alternatives such as private credit in a bid to hit the 7% or so annual return needed to meet long-term liabilities.

In late August, the $25 billion Los Angeles Fire & Police Pensions joined a raft of funds that are adding or raising allocations to the space when it said it would seek to lower portfolio volatility and boost fixed income returns through a 2% private credit allotment. The $41 billion Arizona State Retirement System plans to dedicate $1 in every $6 to direct lending, and the $15.8 billion Ohio Police & Fire Pension Fund said it will cut high yield to move toward a 5% target for private debt, while the $52.3 billion Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System “continues increasing exposures to private debt,” according to a report from Bloomberg. In addition, Frost confirmed that CalPERS will add high-quality private credit funds to its portfolio.

From 2012 through 2019, institutional assets in private credit strategies in the U.S. doubled to more than $800 billion, and they are expected to reach $1.4 trillion by 2023, according to data from Preqin reported by Bloomberg, while last year, 281 U.S. public pensions invested in private credit with a median allocation of 2.9%, up from 186 and a median 2.1% in 2015, according to the London-based research company.

But allocators should look beyond the boundaries of the U.S., where private credit is a crowded space with upwards of 200 managers to Europe, where about 10 participants control nearly 70% of the direct lending market.

Europe’s banks account for about half of all loan capital to the continent’s companies, a far higher proportion than provided by their U.S. counterparts, which creates considerable scope for direct lenders in Europe to increase their share of the private credit space.

Moreover, because European governments turned to the banking sector to fund pandemic guarantee programs, sucking hundreds of billions of euros of liquidity out of the system, many are now trimming or exiting corporate finance operations, including Dutch giants ABN Amro and ING along with Deutsche Bank, Société Générale, BNP Paribas, HSBC and others.

With banks effectively putting up “closed for business” signs, direct lenders have an opportunity to step in and provide capital at attractive yields to high-quality, efficiently managed businesses with predictable and sustainable growth and profit outlooks.

In addition, improving macro data has created a feeling that Europe is over the worst of the economic impact of the pandemic. The German economy is now forecast to contract by a better-than-expected 5.8% this year, while the French central bank said in mid-September that it expected GDP to rebound about 16% in the third quarter.

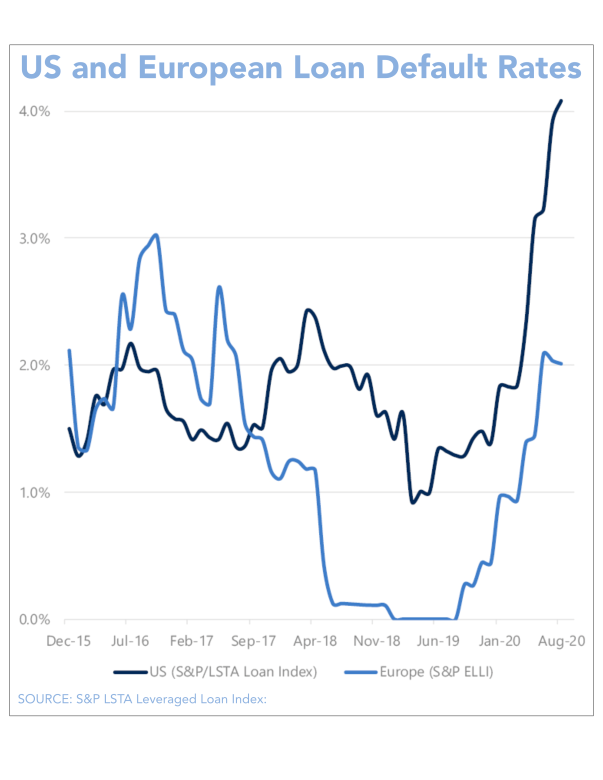

This also helps to diminish a key concern of U.S. allocators about European private credit. Because direct lending in Europe largely took off after the Global Financial Crisis, U.S. institutions have argued that it hasn’t been stress tested. But default rates in the U.S. are running at roughly twice the about 1% to 2% level that Europe is experiencing, according to the S&P LSTA Leveraged Loan Index, partly because European companies entered the crisis from a less levered place than their U.S. counterparts.

That’s not to say that European lenders can be less diligent in their underwriting criteria. The riskiest parts of the market continue to be the “S” in SME, while consumer discretionary sectors such as travel, dining and retail will struggle to raise capital.

But more resilient corners of the market provide opportunities, even if spreads are likely to tighten amid increasing competition as portfolio managers become keener to tell limited partners they are invested in areas that have fared better during the pandemic, including technology, healthcare, food and education.

Currency considerations also improve the attractiveness of European direct lending. After advancing to three-year highs in the first quarter amid a flight to safety, the dollar index hit a more than two-year low on concern about the U.S. budget deficit exploding, hitting $3.1 trillion in fiscal 2020. By participating in hedging programs provided by European direct lenders, U.S. allocators can mitigate currency and interest-rate risk.

So, for U.S. institutional investors seeking to hit their elusive 7% annual target while not adding significantly to risk or volatility, diversifying into funds that provide five- to seven-year floating rate loans to European enterprises with sound credit credentials may be a prudent way to move closer to the goal.

Symon Drake-Brockman is Managing Partner of Pemberton, a London-based asset manager that specializes in direct lending to European companies and is backed by one of Europe’s largest insurers, Legal & General Group.