In 1869, when Thomas Mellon opened T. Mellon & Sons’ Bank, Pittsburgh was as far removed from the central banks of New York, London and Frankfurt as Seattle or Los Angeles. However, during the burst of industrialization between the 1860s and 1920s that transformed America into the world’s leading economic power, Pittsburgh led the way. In the beginning, Mellon and his sons, Andrew and Richard, loaned money based on the value of borrowers’ collateral. In the 1800s, bank lending was based primarily on hard assets.

But T. Mellon & Sons quickly became more than a collateral-focused lender to burgeoning business in Western Pennsylvania. The Mellons were the leading, innovative financial backers in Pittsburgh as it evolved into the Silicon Valley of its day. It was the home of Andrew Carnegie, Henry Frick, George Westinghouse and Henry John Heinz.

The Mellons identified new industries and financed research that drove industrial and scientific breakthroughs from concept to commercialization, such as Westinghouse’s railway air brake and Frick’s steelmaking ovens. Financial innovation by systematically “thinking outside the box” led to the Mellon’s equity stakes in Alcoa, Union Steel (bought by Carnegie for the then-staggering profit of $41 million), Gulf Oil, Westinghouse, Koppers and The Carborundum, to name a few. By 1900, Mellon Bank was the largest bank west of New York City.

Opportunity for Alternative Lenders

Fast forward to 2017. The world is a different place.

“In the aftermath of the 2008 banking crisis, regulators want to discourage banks from taking on ‘equity-like’ risks. This is creating a gap for alternative capital funds to provide financing products that fall somewhere between debt and equity in the capital structure,” notes Floris Hovingh, head of Alternative Capital Solutions, Deloitte, London. At the same time, the search for yield by institutional investors has led to significant inflows into credit funds and non-bank ABL players.

It seems that each month, new alternative lenders launch: Stonegate Capital Holdings in Chicago, Great Rock Capital, CIT Northbridge Credit, Super G Capital, Deerpath, BDCA and Capital Z to name a few.

Commenting on the growth in the European asset-based lending marketplace, Hovingh says, “The market is favoring larger established managers but as the market matures, we will see an increasing number of niche strategies emerging within alternative capital providers. In the UK and Europe, Q1/17 was a bumper one for fundraising, nearly doubling the total quantum of funds raised during 12 months in 2016. It shows continued confidence and growth in the alternative lending market with established players like Alcentra (€2.2 billion/$2.6 billion) and Hayfin (more than €3.5 billion/ $4.5 billion) raising multi-billion funds.”

Because they are publicly traded, many BDCs have tightly focused addressable markets, with little latitude to change direction. Many BDCs are also trading well below par, reflecting concern over credit quality in their portfolios. By comparison, credit funds have the luxury of wider addressable markets, credit boxes and strategies owing to their private ownership status. Consequently, the credit fund sector has seen a flood of fresh money entering.

The New Hybrid

In the U.S., new alternative lenders, such as Stonegate, have a niche strategy. Darren Latimer, partner at Stonegate Capital Holdings in Chicago, says, “We focus on three pillars in the economy: consumer products, food and mission critical software. This specialization allows us to quickly assess the core competencies and risk factors of the borrower and its place in the value chain.”

Alternative lenders are providing a hybrid of collateral-based and cash flow-based financing. The specific structure depends on the cash flow generating capability of the borrower as well as the quality and availability of collateral. In addition to traditional collateral, alternative lenders may finance pro-forma EBITDA and “boot” collateral such as intellectual property, orphan assets, real estate, equipment and litigation claims. Traditional bank-owned asset-based lenders, on the other hand, are more interested in financing accounts receivable and inventory. Specialized equipment finance firms fill the gap in the capital structure by providing better advance rates against fixed assets.

In certain instances, alternative lenders will provide a stretch piece, which may be as large as 50% of the total credit facility. This part of the capital structure is less dependent on collateral and more dependent on cash flow coverage, borrower credit quality and, in some cases, private equity sponsor support. This type of support can run the gamut from springing covenants to “reputational support” — meaning the private equity firm will treat the lenders fairly and not leave them high and dry. For borrowers that demonstrate reliable cash flow, large stretch pieces are commonplace. For companies whose cash flow is choppy or cyclical, stretch pieces can be more difficult to obtain. For borrowers whose business model may be in question, such as electronic products retailers, stretch pieces may be based solely on boot collateral.

Steven Chait, managing director and head of Wells Fargo Capital Finance, EMEA in London says, “Private equity groups are very familiar with the leveraged loan market. If, however, the leverage loan market for some reason does not give the private equity group what it is looking for, it may consider either an ABL or an alternative lender depending upon what is required. ABL solutions work best in situations where companies are going through a strategic transition or are reliant on seasonal business.”

Dan Karas, chief lending officer, TBK Bank, Dallas, notes, “The reemergence of non-bank ABL and alternative lenders fills a much needed vacancy created through bank acquisitions. Fremont, Finova and Congress Financial were just three of many lenders that filled a crucial place in the market for challenged and broken wing companies. The growth of alternative, non-bank, asset-based lenders has expanded market capacity rather than become a hindrance to our business model. Small funds with an appetite for inventory, second lien and subordinated debt fill a gap on the risk spectrum that exceeds my tolerance, but for whom the borrower would not be able to generate sufficient liquidity to execute to plan, most frequently a turnaround plan.”

Twenty years ago, many legacy ABL players focused exclusively on collateral coverage and didn’t care about leverage ratios. As long as the borrower had ample collateral headroom, lenders were less focused on the capital structure. In today’s regulatory environment, bank-owned ABL players have to carefully monitor leverage ratios.

When the Lines Blur

But danger can lurk in the grey area — is this a cash flow loan or a collateral loan? If the lines are blurred and the lender doesn’t have a clear idea, warning signs can be downplayed or missed altogether. For example, a term loan that is heavily collateralized by trademarks and a brand name can go south without the lender realizing the danger, because the warning signals may be nuanced and difficult to detect.

Many alternative lenders are focusing heavily on private equity sponsored transactions. The appeal of PE-backed borrowers starts with a more sophisticated finance and accounting function. This has an important side benefit: Typically, lenders experience less fraud than at companies owned by second, third and fourth generation families.

Latimer explains, “PE-sponsored companies will generally have a more sophisticated capital structure. We are finding in Stonegate’s niche — deals in the $5 million to $15 million range — PE sponsors are finding a rich vein of ore, so to speak. We are seeing a multitude of interesting deals in the lower middle market segment. We’re happy to say there is a much higher level of sophistication in most aspects of borrowers compared with your average family-owned business.”

Jeff Knopping, managing director at New York-based Benefit Street Partners, says, “Private equity transactions are driving a significant amount of asset-based and alternative lending today. One noticeable trend is heightened due diligence given elevated valuations, which are persisting across the market. Alternative lenders can provide the transaction sponsor with good visibility to map out the pro forma capital structure. They can sharply define the balance of traditional ABL players versus alternative lenders in a transaction at a fairly early stage. This can be crucial in developing the contours of the overall financing strategy. Additionally, alternative lenders can provide the advantage of early commitment to a transaction, as well as simplicity and flexibility.”

Partha Kar, partner, Kirkland & Ellis, London, says, “Alternative lenders can play a valuable role in either providing a full package of, or rounding out, the financing to the borrower, especially in Europe where credit enhancement can be tricky. These lenders may appear to cost more than traditional lenders, but experience shows that they can be less rigid on non-financial terms such as covenants and more flexible on other key terms, such as security and upside sharing through PIK interest and warrants. Some also have developed a reputation for being less prescriptive or more accommodating where the borrower may be in financial difficulties.”

“In Europe, it is not quite as straight forward as it is the U.S. to blend ABL with an alternative term loan. It can, however, be done, but there are subtle regional differences in the security arrangements and there are fewer market exemplars to benchmark,” Chait says.

European Bolt-ons Focus

With sky-high valuations, where are the hunting grounds of PE groups and asset-based lenders? “With today’s frothy multiples, it can be a challenge for a PE fund to finance organic growth for a single company on a stand-alone basis. Many private equity sponsors and lenders are focusing on bolt-ons in the middle market to put their money to work and expand,” adds Piero Carbone, partner, McDermott, Will & Emory, London. “In Europe, competition is particularly fierce to finance bolt-on acquisitions by private equity groups. This is particularly evident where there is an orphan consumer products company that is languishing in a conglomerate.”

Alternative lenders like bolt-ons because operating synergies and growth can be more easily identified. Bolt-on transactions may be a better fit with alternative lenders if there’s the need to finance pro-forma EBITDA, which many traditional lenders shy away from.

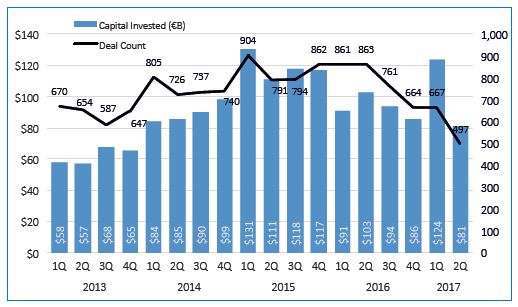

However, “The PE M&A marketplace in Europe is quite tentative right now because of Brexit,” according to Garret Black at Pitchbook in London, “which has led to slowdown in deal volume, as shown in the chart:”

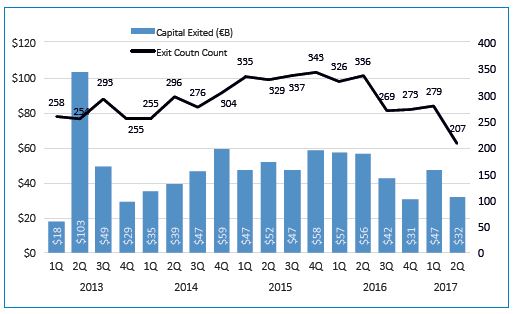

“Private equity exits in Europe were 207 in Q2/17, down from 336 in the prior 12-month period, which reflects the lingering uncertainty in the marketplace,” Black says. “Uncertainty makes valuations challenging.” This is particularly true when the uncertainty over Brexit makes it difficult to distinguish between one-time influences on a company’s P&L.

Chait offers a different perspective: “Although the deal count is falling, average transaction sizes have increased (H1/16 = €112 million/$133 million, H1/17 = €176 million/$209 million), which suggests that the disconnect on valuation is more at the smaller end, and that the larger end is actually quite robust.”

Is the ABL Market Softening?

A pressing question for both ABL and alternative lenders in the UK and Europe is whether demand for asset-based loans is softening or not. According to the Wall Street Journal, a recent survey by Deloitte in London covering Q2/17 showed that UK business leaders’ moods have soured. A third of CFOs surveyed said they expected their capital expenditures to decline over the next three years. With the heavy UK focus of U.S. asset-based lenders, this may act as a damper on loan demand by UK borrowers.

With some concerns that the credit cycle has peaked, many ABL players welcome the involvement of alternative lenders who have a strong credit culture honed over many credit cycles. They can benefit from another set of eyes and ears looking at a proposed transaction, spotting any weaknesses in structure or in the credit quality of the borrower.

This wasn’t always the case. In the early 2000s, two catastrophic frauds shook the asset-based lending community: American Tissue and Alou. Both companies had multiple lenders in extremely complicated capital and corporate structures. While the first lien asset-based lenders felt secure, the sheer number of alternative lenders in dizzying interlocking corporate entities allowed the two companies to confuse the lenders, and ultimately perpetrate the frauds. For example, American Tissue had pledged parts of a large paper machine to 16 different lenders! Alou had a corporate structure that looked like the piping on a nuclear power plant, leaving lenders with a loss of $130 million in 2002. These disasters left bad tastes with ABL players about participating in deals with alternative lenders.

Today, alternative lenders and ABLs are more appreciative of one another. Many ABL players find that alternative lenders welcome their “hard wire brush” approach to collateral. Also, in transactions that have some hair on them, alternative lenders appreciate the fact that legacy ABL players may have a well-documented history of how collateral performs when a company goes sideways. In a good working relationship, seasoned ABL players can quickly communicate that critical information about collateral to the alternative lenders in a crisis.

“Compared to term loan lenders, banks tend to have greater resources to monitor the triggers that may impact value,” Chait says. “Early adverse warnings — such as products being faulty or not selling well — influence cash flows received due to the necessary discounts needed to entice customers. With Wells Fargo’s expertise and resources, we regularly leverage our platform to offer covenant light solutions that support corporates, and we also monitor their operations via sales and collections data. Through our experience, customer relationships and data feeds, we are able to quickly respond to our customers’ changing circumstances.”

Complementary Opportunities

Many ABL industry players think only 25% of transaction opportunities they see are direct competition with alternative lenders. The balance of the deals represents complementary opportunities. In those “Red Ocean” cases where the lenders are all going at each other, often the alternative lenders don’t feel that the collateral or cash flow supports a second lien position. The alternative lenders feel that it’s better to take all of the collateral and do a bigger stretch piece.

“We don’t often compete with alternative lenders directly because their risk/return profile is different than my sweet spot in a supervised institution,” Karas notes. “I’m happy to have a symbiotic relationship where their borrowers with demonstrated improvement graduate to the lower cost structure we can provide, while my borrowers with low effective loan-to-value assets but weak financial performance can migrate to those organizations.”

Jeremy Harrison, regional group head of Bank of America Merrill Lynch, London and president of CFA Europe, says, “One of the goals of CFA Europe is to provide a platform for dialogue between alternative, direct lenders and the bank-owned ABL players. It’s crucial that both groups understand how to offer the best of both worlds to the borrower and how to work constructively together if things go wobbly. We think the two groups can support the needs of the PE and middle market borrower community by providing long-term flexible financing facilities that maximize liquidity and support the anticipated growth of their companies. In many cases, the combination of alternative lenders and ABL lenders can provide PE sponsors with a bespoke solution, which maximizes the debt capacity of the portfolio company. In the minds of some sponsors, asset-based lending is too constricting. The right combination of bank ABL and alternative lenders can demonstrate to PE firms how to wring the most out of their companies’ current assets.”

Another reason why alternative lenders and ABL players are important to one another is that alternative lenders do not have the operational “back office” capabilities to provide revolving credit facilities to borrowers. This is the knife and fork of ABL players. In Europe, Pan European asset-based loans are the Holy Grail. Seamless back office functions across European borders are crucial to realizing this goal.

Opportunities are emerging for good working relationships between ABL players and alternative lenders. What are the challenges?

Credit funds and bank ABL groups have different heritages and, therefore, different credit cultures. When a borrower is flashing warning signs of early decline, the goals, pressure points and timelines of the two types of lenders may diverge quickly and widely. The first lien lender may stop funding because the risk rating of the borrower has deteriorated, whereas the second lien lender may want to meter cash in to protect enterprise value.

Let’s say the company starts to go sideways. Like the famous “Who’s on First” comedy routine of Abbott & Costello, who has what rights to do what when?

Perils of the Unitranche

One area where ABL players and alternative lenders often find themselves at odds is the unitranche space. Typically, the ABL player is the first-out lender, with the alternative lender acting as last-out lender.

“In a typical first-out/last-out unitranche transaction, the collateral rights are usually clear. The allocation of payments and collateral collections under the waterfall is also usually standard. The area where we spend most of the time negotiating is on the actual waterfall triggering events, bankruptcy-related provisions and the standstill provisions,” says Daniel Ford, partner, Hahn & Hessen, New York. “Some ABL players need to come up the learning curve to understand that their credit facility is like the top of a submersible drilling rig sticking out of the water. The rest of the capital structure may be submerged but it’s present and vital nonetheless.”

Knopping goes even further: “An ABL player may lend the company on a 2X EBITDA basis. Side by side, you will have an alternative lender who has lent on the basis of 5X EBITDA. Who controls decision making in a default? In certain circumstances, an alternative lender may be more patient, in order to preserve enterprise value. In some recent transactions, the rights of the parties partially depend on the amount of collateral headroom. If an ABL player is only advancing 50% against eligible collateral, then the ABL player will have a limited amount of rights. If the ABL player has advanced 85% against the eligible collateral, then the ABL player may have a louder voice at the bargaining table, particularly if they represent a larger percentage of funded debt.”

“We like private equity groups that are not afraid to take the keys to the business when a minority ownership situation goes sideways,” Latimer says. “We see ourselves almost like investors as opposed to lenders, so we have a strong desire to ensure that enterprise value is maintained.”

“An important part of negotiations early in the process of ABL players and alternative lenders working together is expectations about behavior if things go sideways,” adds Leonard Lee Podair, Hahn & Hessen Finance partner, New York. “One innovative tool to defusing a crisis between lenders is the obligation of the alternative lender to buy the first lien loan at a predetermined price within a specified period of time if a default occurs.”

In the smaller end of the market, sharing collateral can be challenging. “Merchant cash advance businesses, or MCAs, which are often criticized and maligned, are client-friendly for asset-based borrowers because of their speed and ease of use. MCAs provide cash to businesses in anticipation of the collection of future credit card sales, i.e. for restaurants. They take a lien on A/R, lend the borrower funds in advance of the A/R creation, then have a priority lien if a factor or ABL lender provides working capital financing. However, by usurping the very same collateral in which we place primary reliance, their presence frequently prevents us from doing a deal. The prior lien typically blocks the transaction’s consummation,” Karas says.

In Europe, a critical milestone for both types of lenders is developing standardized documentation in cross-border transactions so all players have a very clear roadmap for closing. European banks like ABN AMRO have dedicated teams that are driving toward seamless documentation and operating procedures for Pan European asset-based loans. Complicating matters will be the final legal framework determined by the Brexit negotiations, which promise to be challenging over the next two years.

Talent Moving to Alternative Lenders

In the past 10 years, there has been a significant migration of talent into alternative credit funds. With many banks facing moderate revenue growth, bank management teams have been forced to manage costs ruthlessly. Entire investment banking teams have been cut from big banks. Many alternative lenders are providing attractive, reliable careers for credit and business development professionals as the investment banking and traditional corporate/commercial/asset-based lending sector continues to face intensified competition and regulatory oversight.

“Great Rock Capital offered me the opportunity to join a creative and dynamic team focused on growing a platform to better service the needs of middle market companies,” notes Lori Potter, managing director of Originations, Charlotte, NC. “I’m excited that we can provide fast, flexible and creative financing solutions to maximize our customers’ liquidity to enable them to better execute their business plans.”

Hovingh offers a final thought from London: “The European Central Bank issued its final guidelines on leveraged lending in Europe, restricting bank completing deals at over six times the adjusted leverage in line with U.S. regulation. Whilst this is only relevant for a smaller part of the leveraged loan market, it gives a clear signal of the direction of travel.”

Thomas Mellon nearly lost his net worth in the Panic of 1873 — an economic depression in which half of Pittsburgh’s 100 banks closed their doors — but he prevailed and was well placed to prosper when the economy again began to expand. By the mid-1920s, he was one of the wealthiest people in the U.S. and the third-highest income tax payer behind John D. Rockefeller and Henry Ford. His son, Andrew, was one of the nation’s foremost art collectors, who gave his priceless art collection to the U.S. government in 1937 to establish the National Gallery in Washington. Andrew Mellon did not insist on his name adorning the National Gallery, an act of self-effacement that has not been surpassed by any philanthropist. He was, no doubt, reminded daily of the philosophy of his father’s inspiration, Benjamin Franklin, whose life size statue stood above the cast iron door of the original bank building at 145 Smithfield Street in Pittsburgh. And like Benjamin Franklin, the Mellons built their reputation on innovation and a willingness to take risks.