Herrick Feinstein

Given the continuing and widespread weakness in the retail industry, investors’ focus has shifted to the real estate occupied by stores. With substantial equity and debt capital invested in retail real estate, investors have to wonder, are regional shopping malls the next troubled asset class? The health of shopping malls is closely tied to the health of the retail industry, which faces multiple problems, including the rise of electronic commerce, store closings, declining pedestrian traffic, changes in consumption patterns and weak consumer incomes. While these pressures are not new, their combination is intensifying the pressure on retailers, which in turn affects mall owners.

According to the International Council of Shopping Centers, there are approximately 1,200 regional malls in the U.S. Earlier this year, Credit Suisse published a report stating that as many as 300 malls are likely to close within the next five years, while other analysts have suggested as many as half of all existing malls will close. Some industry observers are less pessimistic, arguing that the shopping mall industry is bifurcating into a group of high performance properties, which will continue to perform well, and that the industry’s problems are confined to the weakest malls. Facing these challenges, mall owners must make difficult choices and adapt their properties to the changing retail environment or accept that some properties may be beyond rescue and surrender them to lenders. The dilemma is no easier for lenders, who typically experience steep loses when they foreclose and are faced with the decision to sell or refurbish.

Investors Pessimistic About Shopping Malls

The current gloom about shopping mall prospects is evident on Wall Street, as equity and debt investors have soured on shopping center investments, and the shares of shopping mall real estate investment trusts (REITS) have fallen sharply in the past year. Figure 1 shows how eight shopping mall REITS have performed over the past year. The declines have ranged from roughly 20% to more than 40%, with the decline in share prices accelerating over the past six months.

Investors also are wary of commercial mortgage-backed loans (CMBS) to shopping centers, due to their declining performance. According to Morningstar Credit Ratings, as of Q4/16, approximately $3.8 billion in shopping center loans were in default, representing approximately 7.8% of the $48.6 billion market for such loans. Beginning in the spring of 2017, hedge funds and other investors began to increase their short positions against shopping center CMBS loans. In Q1/17, traders bought a net $985 million in credit default swaps that target the two riskiest types of CMBS, according to the Depository Trust & Clearing Corp. That’s more than five times the purchases in the prior three months. In September 2017, Fitch Ratings also warned that Amazon’s increasing market share in apparel sales could result in more retail CMBS defaults.

Investor concern with shopping center CMBS loans is understandable. In 2016, the dollar volume of CMBS defaults was up approximately 11% over 2015 levels, and shopping center loan foreclosures have generated large losses for investors. According to Morningstar, since 2010, there have been foreclosures on CMBS shopping mall loans with a face value of $2.88 billion, with noteholders losing 74 cents on the dollar. Recent shopping center CMBS loan liquidations are consistent with Morningstar’s research. In March 2017, a $62.7 million loan on the Citadel Mall in Charleston, SC was foreclosed, with a total loss on the property, and in August 2017, a $64 million loan on the Hilltop Mall in Richmond, CA was foreclosed, resulting in a 78% loss.

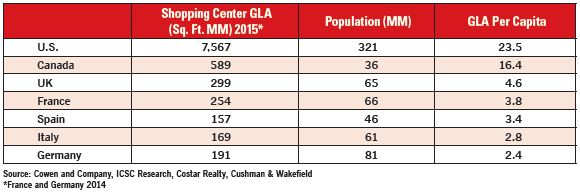

Cowen predicted that the future increases in e-commerce and the continuing wave of store closures will contribute to the number of mall closures and eventually result in the U.S. having a per capital GLA of shopping center space closer to the levels of peer economies.

One obvious pressure on malls is store closings. While 2016 saw many retailers announce store closings, including Macys (140 stores), Hancock Fabrics (250 stores), Sports Authority (460 stores), Aeropostale (570 stores), Sears/Kmart (approximately 80 stores), J.C. Penney (40 stores) and Office Depot (up to 300 stores over three years), the pace has accelerated in 2017. Through the end of July, approximately 6,400 store closings were announced and Credit Suisse projects the final tally will be approximately 8,700, eclipsing the previous high of 6,163 in 2008. The most critical loss for shopping malls has been the weakness in department stores, the traditional anchor tenants, with Macy’s, J.C. Penney and Sears among the leaders in store closings.

Retailers that file for bankruptcy have been particularly active in closing stores. Few retailers reorganize under the Bankruptcy Code; most often they are either liquidated or sold to new owners. But even when retailers are sold as going concerns, they use the Bankruptcy Code to reject unprofitable store leases. Aeropostale, for example, operated nearly 800 U.S. and Canadian stores when it filed for Chapter 11 in 2016. While Aeropostale was sold to a consortium of new owners, the group included mall owners Simon Property Group and General Growth Properties, which participated to keep more Aeropostale stores operating. Even so, Aeropostale trimmed some 300 stores in bankruptcy. Retailers that have sought bankruptcy protection in 2017 include Toys “R” Us, The Limited, Wet Seal, Eastern Outfitters, BCBG Max Azria, Vanity, HHGregg, RadioShack, Gordmans Stores, Gander Mountain, Payless, Rue21 and Gymboree. Analysts believe that Toys “R” Us is likely to close stores after the 2017 holiday season. Persistent market rumors that Sears, Kmart, and J.C. Penney may also seek bankruptcy could lead to still additional closings.

Store closings hurt mall operators in at least three ways:

- An immediate loss of rental income

- New tenant(s) may require the landlord to provide improvements, creating potential cash drains

- In the case of anchor tenants, store closings may reduce overall pedestrian traffic, which affects rents received from remaining in-line stores

When leasing markets were stronger, mall operators could easily replace a departing anchor tenant. But with department stores now at the forefront of the store closure wave, that alternative looks increasingly unlikely.

The loss of anchor tenants also reduces mall traffic, which affects all retailers, not just anchors. Anchor tenants historically paid low base rents, whereas in-line stores paid “percentage” rents based on their gross receipts. As mall traffic declines, so does the percentage rent paid by these tenants. The traffic decline has been stunning. In 2010, there were 35 million visits to malls, according to Cushman and Wakefield. By 2013, there were 17 million visits — a 50% decline. More recently, Cowen reported that since January 2014, U.S. mall traffic has declined every month except March 2015, with the average year-over-year decline at 5.3%.

Weakness in the Retail Sector

Much of the weakness in shopping malls is directly attributable to disruption affecting store-based retail. However, the overall weakness in the retail sector has several causes: the growth of e-commerce, changing consumption patterns and stagnant consumer incomes.

Much of the retail industry commentary has focused on the rise of e-commerce, because the growing share of e-commerce is the most visible change and the easiest to measure. E-commerce penetration as a percentage of total U.S. retail sales has steadily increased over the past decade from 2.7% of total sales at the beginning of 2006 to 8.3% by the end of 2016 — more than tripling over the past decade. More specifically, the rise in U.S. e-commerce can be tied directly to its behemoth, Amazon. According to a recent Cowen report, 82% of consumers reported visiting Amazon’s site within the past 30 days and 49% said they or a household member were an Amazon Prime customer, up from just 18% in 2012. Overall, Cowen believes that e-commerce will account for 9% of U.S. retail sales in 2017 and could reach 14% by 2022.

While those projected increases will affect all retailers, Cowen predicts that online apparel sales could reach 40% or more of the market. That penetration is backed up by research from retail advisor NPD Group, which reported online sales made up 11% of total U.S. apparel sales in 2011 but 19% in 2016. If this trend continues as predicted, mall-based retailers will clearly suffer.

Changes in consumer spending are also contributing to the decline. A generation ago, consumer spending on clothing, a staple of mall sales, was in the range of 5% to 6% according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, but prior to the U.S. financial crisis, only 3.5% of consumer spending went toward clothing. Since 2005, household clothing spending has declined by nearly 10%, and it now stands at the same dollar level as in 1995.

Consumer spending is also shifting from the purchase of goods to services, entertainment and travel. Macy’s CEO Terry Lundgren recently said that consumer spending “is in automobiles, housing, health care and certain apps that they are downloading.” Another analyst explained the change in consumption: “There’s less focus on image and apparel and more focus on electronics,” said Marshal Cohen, NPD Group chief industry analyst. “The millennial and post-millennial is very focused on being connected. Getting connected is already hundreds of dollars per month,” said Cohen. “That used to buy jeans. It’s not buying jeans anymore.”

BLS’ data supports that view: entertainment spending has risen as a percentage of consumer spending while apparel sales have fallen. Americans are also spending more money on travel and restaurants. According to the U.S. Travel Association, Americans were projected to spend $802 billion in 2015 on leisure travel, and according to MasterCard, travel spending has risen 14.5% since 2011. Restaurants have also outperformed retail same-store sales, according to Thomson Reuters.

Weak growth in consumer disposable income is another factor affecting retail sales. Although the economy has expanded since 2013, for most of the past decade consumers have experienced only modest income growth, and per capita disposable income has been largely flat for the past decade. Even with the growth since 2013, the compound annual growth rate over the last 10 years has been approximately 1.1%, a level far below the post-World War II average of nearly 3%. Over the same time period, the cost of living has continued to increase for middle-class consumers, and the combination of weak growth in income and increased costs have made consumers cautious about spending. In addition, rising health care costs have cut into disposable income. Since 2010, per capita health care expenses have doubled from $4,500 to $10,000.

Changes in Mall Formats

The rapidly changing retail sector poses a challenge for mall owners and shopping center lenders. A typical regional mall contains approximately 110 acres, including a ring road, a large parking lot and water and power utilities to service it. For a mall in transition, such as one that has lost one or more anchor tenants, the owner can choose to walk away from the existing investment or try to adapt the space so it can continue to be productive. From an owner’s or lender’s perspective, walking away is rarely attractive. Thus, within the shopping mall industry, the race is on to figure out the best way, if any, to adapt shopping malls.

There are many ideas for re-purposing malls but few perfect answers. Some malls have simply tinkered with store and amenity mix and added varied dining and entertainment options. One advantage of these limited makeovers is that they do not require substantial capital improvements, but their weakness is that they don’t address the fundamental changes taking place in retail.

Other approaches look at bigger changes to the physical mall environment or the kinds of businesses or services offered. According to retail analyst Ray Hartjen of the advisory firm RetailNext, options include incorporating non-retail activities, such as community college spaces, houses of worship or fitness facilities. Other possible new mall tenants include medical and dental offices and clinics. Other suggestions include using existing store space for “pop-up” public events or using a portion of a mall’s space for farmers’ markets. In a different direction, some analysts have advocated turning some or all of a mall’s space into housing, while others advocate using mall spaces as fulfillment centers for e-retailers.

One example of adaptive reuse is the Hickory Hollow Mall in Antioch, TN. In 2011, the last of the mall’s two remaining department stores announced closings — within days of each other — and by June 2012, the mall had shuttered. But it recently reopened under a new name, Global Mall at the Crossings, and with a new strategy. In addition to traditional mall stores, the center now contains a satellite campus of Nashville State Community College, a library, a recreation center and, perhaps most unusual of all, a practice rink for Nashville’s NHL team.

Another example is The Arcade in Providence, RI, an indoor mall modeled after European arcades. With its center city location, The Arcade was unlike a traditional suburban property. But it had fallen on hard times, and in 2012 it closed for two years of renovations. A dozen or so local shops — no chain stores — still occupy the first floor, but the top two floors were completely gutted and turned into microlofts — small one-bedroom apartments.

Not all attempts to readapt malls have succeeded. The Erieview Mall in Cleveland, had a vaulted glass ceiling that admitted abundant natural light. When the mall’s shops began failing, its management turned parts of the mall into the greenhouse it resembled. Starting in September 2010, herbs, salad greens and fruit were grown hydroponically in the mall’s glass atrium, while old jewelry stalls were repurposed as gardens on wheels. The project, Gardens Under Glass, was lauded in the New York Times and National Geographic. Yet Gardens Under Glass also illustrates the risks of radical changes. The mall’s temperature-controlled indoor climate proved to be a breeding ground for aphids. With poor yields and management difficulties, the gardens were gone two years later.

Experimenting with mall formats is a process that has just begun, and no single replacement model has emerged as the dominant alternative. Given the wide gamut of communities that malls serve, ranging from central urban locations to exurban and rural sites, it is conceivable that no single format will emerge. But there is one point that analysts agree on: change is coming soon, particularly for the weaker B and C properties that make up the lower tier of the U.S. shopping mall universe.

The Future & Consolidation

Although the stresses on the shopping center industry are clear, analysts differ on how severe the impact will be. On the negative end, commentator Howard Davidowitz of Davidowitz & Associates predicts half the 1,100 U.S. regional malls will close over the next decade, while Credit Suisse has pegged the likely closure total at 300 over the next five years, and Cowen believes 240 malls will need to close. Other analysts are more sanguine about the long-term outlook. Despite the weariness in the market, the notion that the end is nigh for brick-and-mortar retail is overstated, acccording to analysts at industry research firm Trepp, which predicts e-commerce giants will slowly open physical stores or showrooms and retail landlords will adapt to fill the space left behind by big-box tenants.

Others see the weakness as an inherent condition of the market. “Every conference I go to, they talk about a softening of the real estate market in 2018, 2019,” said John D’Amico of Trimont Real Estate Advisors. “That’s just the cycle. It’s about the right time. It won’t be like 2008 to 2010, but there will be a softening.” Although it recognized that some mall closings would occur, Cowen argued at the same time that the problems in the shopping mall industry are largely confined to class C and D malls, and that class A and most class B malls will survive. Green Street Advisors has a similar view, believing higher-end malls will continue to see growth in net income, but primarily from renewing store leases at higher base rents, rather than from increased percentage rent from tenants. As a consequence, Green Street reports mall values for higher-end malls are holding steady, but values for B and C malls appear to be softening. Green Street further notes that there has been a “transaction void” in sales of lower-rated mall properties, a further reflection of buyer concern.

So, while opinions differ about the extent of the problem, it’s clear that the industry expects the next few years will be challenging, with an increase in loan defaults and further weakness in the underlying retail sector. What is less clear is the optimal solution to the continuing pressures.