Managing Partner

Pemberton

Consider this fictional example: The CEO of Eine Kleine GmbH can’t borrow the €100 million ($118.07 million) she wants to develop the German family-owned company’s technology and consolidate its 50-year domination of U.S. archrival Itsy Bitsy in the automotive safety testing equipment market.

The public debt markets may not be an option because no one wants to go through the regulatory processes and underwrite and market a high-yield bond issue of that size. Commercial banks interested in syndicating a loan of under €250 million ($295.18 million) for a mid-size family-owned company with €180 million ($212.53 million) in revenue aren’t an option either, even though the company’s sales and net income have been climbing steadily and predictably every year.

Fortunately, there is another option. The market for direct lending to private, mid-size European enterprises has expanded significantly since the global financial crisis in 2008, providing a valuable source of capital to companies such as Eine Kleine, or at least the real companies Eine Kleine represents in this example.

Room For Growth

The direct lending asset class in Europe is far from mature, according to the European Direct Lending – Review and Outlook Report by Saïd Business School, Oxford University, and is set for further significant growth.

That isn’t a stretch, according to the report’s authors, with industry analyst Preqin forecasting that assets under management in global private debt funds will surpass $1 trillion this year after hitting $887 billion in 2020, making it the third-largest private asset class behind private equity and real estate.

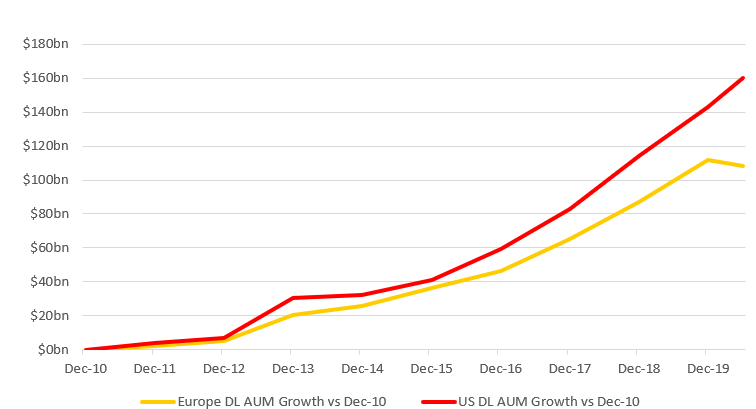

The assets under management of European direct lending strategies rose a hundred-fold to $112.3 billion in June 2020 from $1.5 billion at the end of 2009, according to Preqin, making direct lending the largest private credit category in the region.

Comparison of Direct Lending AUM Growth for Europe and the U.S. Since Dec. 2010*

Tailwinds

According to the Saïd Business School-Oxford University report, which was commissioned by Pemberton to analyze the greater marketplace, the explosion in AUM and direct lending’s ascendancy to the top of the asset class in Europe has been fueled by four key drivers: a continuation of the decades-long decline in yields on publicly traded debt, regulation and consolidation in the banking sector, a surge in the number and value of private equity-backed buyouts and rising demand from mid-size enterprises.

Growth in direct lending, which is defined as non-bank senior secured loans to sub-investment-grade companies from €25 million ($29.52 million) to €300 million ($354.29 million), has accelerated as more onerous regulation has led to the withdrawal of $3 trillion in domestic credit from non-financial sectors by Europe’s banks since the global financial crisis, according to the report, which noted that the decline in corporate finance provision is only likely to accelerate under the full implementation of Basel III and Basel IV global bank capital requirements.

Consolidation Wave

The global financial crisis focused the boardrooms of banks from Madrid to Frankfurt on domestic and cross-border consolidation. Between 1998 and 2016, the number of banks in Germany and France fell by 50% and 60%, respectively, according to the report, while the merger between Spain’s Caixa Bank and Bankia led a surge in M&A activity among European regional banks to $37 billion from July to mid-December 2020, according to Bloomberg.

The consolidation process is likely just beginning, with mega tie-ups between France’s BNP Paribas and Société Générale, Spain’s Santander and BBVA, Switzerland’s UBS and Credit Suisse and the UK’s Barclays and Standard Chartered the subject of discussion by M&A bankers and lawyers across Europe’s major financial centers.

As banks step away from corporate finance, both mid-size companies and private equity funds are increasingly turning to institutional platforms for the capital they need to fund buyouts, recapitalizations and growth, according to the report.

Diversifying the Base

While Europe’s buoyant private equity industry has historically been a key source of business, with 81% of the 416 direct lending deals in Europe in 2018 involving a private equity sponsor, according to Deloitte, mid-market enterprises with EBITDA from €10 million ($11.81 million) to €50 million ($59.05 million) are an increasing source of business and therefore diversification.

Direct lending provides several advantages for borrowers over syndicated or ‘club’ deals. The expenses derived from rating and marketing a public issue and meeting regulatory requirements are significantly reduced or eliminated, agreements can be tailored to the characteristics of the borrower’s business and the time taken to conclude a transaction is much shorter, as borrowers deal with only a single originator.

Premium Opportunity

Many private equity funds and corporate borrowers are prepared to pay a premium for such benefits, which in turn can filter through to improved returns over treasuries, investment grade and high yield bonds and syndicated loans.

Direct lending funds had a median net internal rate of return (IRR) of 9.2% between 2008 and 2016, according to Preqin, with a typical premium over the LIBOR between 5.5 and 7.5 percentage points. That compares with a spread of 3.75 to 4.5 percentage points for syndicated loans. As a result, European direct lending funds are projected to provide returns 3.5% higher than syndicated loans, with margins of 5.5 and 7.5 percentage points above LIBOR.

Capital Preservation

Unlike buyout funds, direct lenders can’t rely on rising equity values to boost returns. The best fund managers are therefore firmly focused on capital preservation through downside protection. That means robust covenants and term sheets, capital structure seniority, detailed monthly information provisions from the borrower and the right to intercede to amend business practices and cost structures should ongoing credit monitoring highlight a potential issue one or two quarters down the line.

Unlike high yield or levered loan investors who have little control over the credits they own, borrowers from direct lenders can’t spin off profitable assets to leave creditors holding capital-draining units or a balance sheet weighed down by liabilities. Holders of senior secured loans have a direct relationship with the borrower, allowing them to flag warning signals earlier.

As a result, investors in direct lending funds have better protections from the biggest enemy of credit provision: dithering. As those who have spent a lifetime in the corporate finance world know well, early action preserves capital.

For direct lending funds, institutional investors starved of fixed-income yield, private equity firms eager to put assets to work and mid-size companies that need access to growth capital, the downside protection benefits may ultimately be the biggest benefit the direct lending asset class holds over its counterparts in the public debt markets.

Symon Drake-Brockman is managing partner of Pemberton Asset Management, a European private credit provider that specializes in direct lending to mid-size companies and is backed by Legal & General Group .

All information in this article is correct as of Aug. 18, 2021