Field examiners often spend considerable time diligently scrubbing a borrower’s trade account receivables (A/R) by performing, among other procedures, confirmations, testing of invoices, shipping, credit note, partial payments and review of customer agreements and analysis of accounting reserves. These procedures lead to the formulation of a list of potential borrowing base (Bbase) ineligibles for the lender. More often than not, the proposed ineligibles are met with some skepticism and the following question “Aren’t these all covered by dilution?” The question may come from a borrower concerned with Bbase availability or an account manager concerned over the impact on a relationship and/or a deal closing. Regardless of the motivation, the answer is critical to ensuring that the Bbase is formulated to adequately protect an asset-based lender’s interest.

The Basics

Prior to answering the question, it would be useful to review the mechanics of an A/R Bbase. A Bbase is simply a calculation that determines the amount that an asset-based lender is willing to lend to a specific borrower. The Bbase utilizes a borrower’s financial information to estimate the realizable value of its collateral in a liquidation scenario. Asset-based lenders rely on two metrics to estimate the A/R liquidation value, namely ineligibles and dilution.

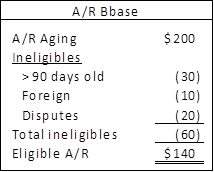

A/R ineligibles represent specific items that an asset-based lender does not wish to lend against due to their associated credit risk. The more common ineligibles include A/R aged greater than 90 days past invoice date, foreign receivables, contra accounts and disputes.

Table 1 reflects a typical A/R Bbase net of ineligibles:

Table #1

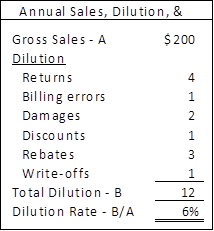

The second metric utilized by the asset-based lender to estimate liquidation value is dilution. Dilution measures the risk associated with the collection of A/R. A dilution analysis attempts to estimate the ultimate collection for every dollar of A/R on the books. The analysis will consider various dilutive elements including credit notes (for returns, errors, damages, etc), write-offs (i.e., for bad debt), payment discounts, as well as customer rebates and allowances. Dilution is impacted by a company’s trade policies, credit and collection procedures, as well as its customers’ financial health and is usually expressed as a percentage of sales (dilution rate) with the most common method of calculation as follows;

Dilution Rate = Dilution/Gross Sales for trailing 12-month period

Examples of dilutive elements as well as a calculation of the annual dilution rate is presented in Table 2:

Table 2

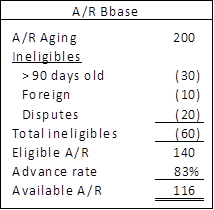

Dilution is critical in evaluating A/R over an extended time period and is an essential metric for asset-based lenders. One of the common methods for calculating the Bbase A/R advance rate takes into account dilution as follows:

Bbase A/R advance rate =100 %-(2*Dilution Rate)-5%

Based on the above example, a company with a dilution rate of 6% would have a Bbase A/R advance rate of 83%. In doubling the historical dilution and adding a further 5%, the advance rate is meant to provide a “cushion” to a lender to protect against the higher collection risk in a liquidation scenario collections are more problematic when a company ceases operations as certain customers demand proof for all shipments, exaggerate disputes, claim damages, etc.

While there are numerous methods of estimating dilution and setting advance rates, we have focused on the more common method outlined above. Accordingly, a typical A/R Bbase for a company with a 6% dilution could be as follows:

Table 3

Aren’t We Double Counting?

A frequently asked question is: “Why do I need all these ineligibles if I am factoring in dilution?” At this point we need to take a step back and consider the purpose of advance rates and ineligibles. Ineligibles are meant to exclude receivables whose collection is doubtful or problematic. Once the “ineligible receivables” have been removed, the advance rate then estimates how much of the “eligible receivables” could be collected in a liquidation scenario. Put simply, ineligibles get rid of the bad receivables while the advance rate estimates how much of the good receivables could turn bad in the future.

While the above is a useful starting point, it leaves a field examiner and account manager with the following question: How does one identify the pool of eligible receivables and ensure that the ineligibles established have not already been addressed by dilution (i.e., the advance rate)?

Breaking Down Dilution

The key to answering this question understands how the dilution calculation works. The dilution rate is calculated based on a historical average that is then applied to the A/R at a point in time to estimate collectability. Accordingly, if 5% of yearly gross sales were dilutive, A/R is assumed to also be 5% dilutive.

This logic only holds if the composition of sales and A/R are equivalent. However the issuance of credit notes and the write-off of uncollectable accounts often lag the collection of “good” receivables. The end result is that the dilution level in A/R is often significantly higher than the dilution rate determined on sales. The following example illustrates this point:

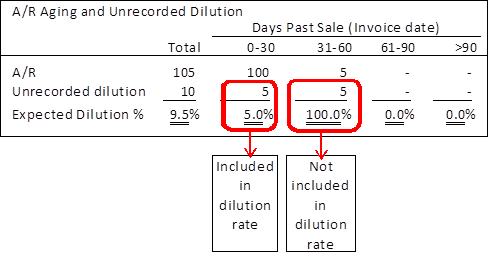

Example #1:

A company generates $100 of sales per month, which is collected 31 days after invoice date. The 31 days is considered the “collection period.” The company has returns of 5% of gross sales each month (dilution rate), which are recorded as credit notes 61 days after the invoice date (credit lag). An A/R aging and effective dilution based on the above assumptions is as follows:

Sales made in the current month are fully reflected in the 0-30 day column of the A/R aging and would include $5 of future dilution (5% dilution factor).

Sales made 31 to 60 days ago (refer to the 31-60 day column above) would have been collected as customers pay in 31 days however as the related credit notes are only issued after 61 days, the 31-60 day aging column would still contain a $5 balance that is uncollectible (i.e., 100% dilutive). This additional dilution is the result of the credit lag.

Accordingly, while the dilution rate is 5% of gross sales, the effective dilution rate on A/R is 9.5% (nearly double the dilution rate!).

Example #2:

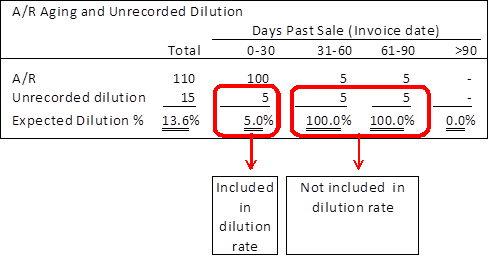

In the above scenario, the gap in dilution due to credit lag is further amplified if the credit notes were only processed in 91 days versus 61 days, as noted in the following example:

In the above scenario, the dilution rate on sales remains at 5%, however the effective dilution rate on A/R increases to 13.6% (almost triple the sales dilution rate).

While most situations involve the collection of A/R prior to the processing of credit notes, there are rare occasions when credit notes are recorded in advance of collections (i.e., extended payment terms). In these situations the sales dilution rate would overstate the effective level of dilution in A/R.

The Dilution Cushion

While the examples above demonstrate that the annual dilution rate is not always an effective measure of dilution in A/R, lenders typically take comfort in the fact that the Bbase advance rate often doubles the dilution rate and includes a further 5% “cushion.”

While this may be valid use of the “cushion” to provide a buffer for credit lag leaves less room for unforeseen contingencies that could occur in a liquidation scenario. In addition a company could inflate Bbase collateral simply by reducing the timeliness of credit note processing accordingly, the cushion may not really exist

A Simple Rule of Thumb for Credit Lag

A simple but often effective rule of thumb for adjusting dilution to account for credit lag is as follows:

Average Credit lag in days /Average Collection time in days * Dilution rate = Effective Dilution on A/R

Utilizing this rule of thumb, the effective dilution rate in examples 1 and 2 would be as follows:

Example 1: 61/31*5% = 9.8%

Example 2: 91/31*5% = 14.7%

While this simple rule of thumb results in a better approximation of the actual dilution, it is not a mathematical proof and may not apply in all instances.

The outline to date leads to our first rule of dilution:

If the credit lag is greater than the collection period, the effective A/R dilution will be greater than dilution based on gross sales.

Now that the first rule of dilution has been established, the next article in this series will focus on field exam techniques used to identify and quantify effective dilution.

Gilles Benchaya is a partner at Richter Consulting Inc., which has specialized over the past 20 years in financial advisory, turnaround and diligence in the retail, consumer goods and distribution sectors. He has led a number of multidisciplinary teams in North America and Europe providing fully integrated transaction support and advisory services to clients. He is a chartered accountant (CA) and graduate of HEC (University of Montreal) Business School. He can be reached at by e-mail at [email protected]

Gregory Anderson is a senior associate at Richter Consulting, Inc. Anderson has extensive experience as an advisor to financial institutions with specific expertise in asset-based lending. He has consulted on field examination and lender monitoring processes as well as loan workouts. Anderson is a CA and Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE). He can be reached at by e-mail at [email protected].

Richter Consulting, Inc. is a member of the Richter Group, a full-service business advisory firm, founded in 1926, with over 40 partners and 400 professionals. The company provides a full range of consulting services delivered by a multi-disciplinary group of professionals. Its services include business assessment, financial reorganization, crisis management, turnaround management, transaction advisory, business valuation, insolvency consulting, forensic investigations, and litigation support.