Introduction

Lenders that extend credit to healthcare companies and providers often include healthcare insurance receivables and healthcare-related accounts in the borrowing base that determines a lending amount. As with all collateral, the lender wants to be secured, perfected and first in priority on these healthcare insurance receivables. Additionally, should the borrower default, the lender wants to be able to foreclose on the collateral and realize its value as payment for the loan.

This article reviews the issues related to extending credit secured by a lien on healthcare insurance receivables and the differences between an account, where the account debtor is the government (i.e., on behalf of the Medicare program), and an account where the account debtor is a private party.

Security Interest in Accounts

Lenders routinely take a lien on accounts as part of the collateral package securing a loan. Pursuant to the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), healthcare insurance receivables are a subset of accounts and considered the same as accounts with respect to the method by which a secured lender obtains a perfected security interest. The borrower or any other person whose property secures the loan will grant the lender a security interest in its accounts (which includes healthcare insurance receivables). This grant of a security interest, and the giving of value by the lender, makes the lender secured and gives it some rights in the collateral.

Additionally, the lender will want to perfect its security interest by filing a financing statement describing the collateral in the jurisdiction where the borrower, or other person granting the security interest (such as a guarantor), is located. The filing of the financing statement perfects the lender’s security interest in the account, and gives the lender priority over any unsecured creditors and any secured creditors that have not perfected.

Being a perfected secured creditor is only part of the battle for a lender. Equally important for a lender is its ability to collect the proceeds of any of the accounts, if necessary. In addition to a lien in the accounts, the lender will also take a lien on, among other things, the cash and deposit accounts where the cash proceeds are deposited when the accounts are paid.

The secured lender must have “control” of the deposit account in order to perfect a security interest in the deposit account and the money in the deposit account. Control exists if: i.) the secured lender is the depository bank at which the debtor maintains its deposit account; ii.) the secured lender becomes the depository bank’s customer with respect to the deposit account; or iii.) the secured lender enters into a deposit account control agreement with the depository bank. A deposit account control agreement is signed by the debtor, secured lender and the depository bank, and provides that the secured lender will have control of the account by virtue of the depository bank agreeing to take instructions from the lender without obtaining consent from the debtor.

Security Interest in Healthcare Insurance Receivables and Medicare Accounts

A security interest in a healthcare insurance receivable can be perfected through the filing of a financing statement. Deposit accounts, where proceeds from healthcare insurance receivables and accounts are deposited, can be perfected through control over such deposit accounts. However, federal laws require that government healthcare accounts, including Medicare and Medicaid, be treated differently from private healthcare insurance receivable accounts in certain ways. As a result, secured lenders must take certain additional steps to protect their collateral or consider limiting the amount of government healthcare accounts that are included in their borrowing base.

Private Health Insurance Accounts

A lender may perfect a security interest in non-government healthcare accounts (i.e., private pay insurance) and the applicable deposit account, where the account payments are deposited, in the same fashion as the process regarding the accounts and deposit accounts discussed previously. In the case of healthcare insurance receivables and accounts, the security interest of the lender attaches to the cash proceeds of such accounts, when the debtor receives the payment. The cash proceeds of the healthcare insurance receivables and accounts should not be commingled with other funds and should remain identifiable in order to perfect a security interest in such cash proceeds.

When a secured lender perfects a security interest in the healthcare insurance receivables and accounts, the secured lender has a right to notify the account debtors to directly make payments to the secured lender if the debtor defaults. Even if the provider agreement between the healthcare provider and the heath insurance company, as the account debtor, restricts assignment of the healthcare insurance receivables, the UCC provides that the grant, attachment and perfection of a security interest in the account does not result in a default under the provider agreement.

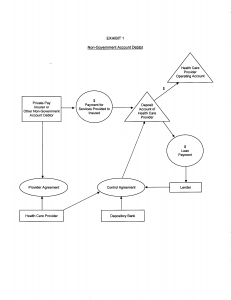

Exhibit 1 reflects the typical secured private pay account structure.

Medicare Accounts

Medicare accounts, as well as the accounts of other government healthcare programs, are subject to anti-assignment rules. These anti-assignment rules prohibit a healthcare provider from assigning its right to payment for services to any person other than the provider. A violation of the anti-assignment rules could result in termination of the healthcare provider’s participation in Medicare or other government programs. Thus the lender may be secured and perfected in the account under the UCC, but it may have practical issues with collecting the cash proceeds, because the lender cannot be paid directly from the government.

In particular, the healthcare provider’s deposit account where Medicare payments are made can only be in the name of the provider, and only the provider is allowed to provide instructions with regard to the account. With Medicare accounts, the debtor will retain the ultimate right to direct the payments of funds into and out of the deposit account. Although a lender cannot have control over the debtor’s initial deposit account containing proceeds of Medicare accounts, the depository bank, secured lender and debtor may sign an agreement, pursuant to which the depository bank agrees to notify the lender if the debtor rescinds the sweep order.

However, if a secured lender perfects a security interest in the Medicare accounts themselves, then the secured lender is perfected in the identifiable cash proceeds of those receivables. As a result, once Medicare makes a payment to a provider, and that payment is deposited in the provider’s account, the secured lender’s security interest is perfected in the cash proceeds for 20 days, despite the fact that the secured lender cannot control the deposit account. It is recommended that the lender require a healthcare provider debtor to deposit its Medicare reimbursement proceeds into a deposit account separate from the non-government healthcare insurance receivables deposit account — in order for the proceeds to remain identifiable. Additionally, the loan documentation should contain covenants that prohibit commingling.

The secured lender will want to obtain control over those Medicare payments by, as quickly as possible, moving the payments into a deposit account subject to the lender’s control. In order to do this, the funds should be swept regularly from the debtor’s deposit account into a deposit account subject to the lender’s control. This is referred to as a “double lockbox arrangement.”

In the double lockbox arrangement, there are some circumstances to keep in mind. The debtor continues to control the initial deposit account and can rescind the sweep order and withdraw money from the initial deposit account at any time. In addition, if the debtor files bankruptcy, the funds may become trapped in the initial account, as the sweeping mechanism may be stayed. As a result, the secured lender should require that the account be swept on at least a daily basis in order to avoid cash proceeds accumulating.

Exhibit 2 reflects the typical Medicare or government pay account structure.

Case Law Interpretation of Anti-Assignment Rules

If the debtor defaults on a loan, federal law preempts non-judicial enforcement of a security interest in government healthcare accounts. However, the Medicare statutes provide for a judicial remedy in order to obtain assignment of the Medicare payments. A secured lender must file suit to enforce its security agreement, and a judge may issue an order assigning the right to Medicare payments to a third party. Such court order, when filed with Medicare, is not a violation of the anti-assignment rules. However, the courts have inconsistently interpreted the Medicare anti-assignment provisions. Some courts provide a flexible interpretation of the anti-assignment provisions and others are stricter.

In Missionary Baptist v. First National Bank, the Fifth Circuit upheld an arrangement where the bank took a security interest in Medicare and Medicaid accounts and, by agreement, received direct payment of the accounts. The Fifth Circuit held that this did not violate the anti-assignment rules. Missionary Baptist is the foundation for several cases, which conclude that the anti-assignment rules were not intended to invalidate security interests in Medicare and Medicaid receivables, so long as the provider has control over the initial payment from the government.

In DFS Secured Healthcare Receivables Trust v. Caregivers Great Lakes, Inc., the Seventh Circuit discussed the history behind the anti-assignment rules, finding that “nothing suggests that Congress intended to prevent healthcare providers from assigning receivables to a non-provider.” In fact, the court noted that in this case, Medicare was aware of the assignment of healthcare accounts between the provider and a non-provider third party, and that there was no evidence of any disapproval of the assignment.

In the case, In re Nuclear Imaging, the court discussed the double-lockbox arrangement, but stressed that the secured lender has no legal right on its own to demand payment from the government. Once a default situation arises, the secured lender cannot directly obtain payment from the government and will only have a security interest in the payments that have already been swept into the deposit account it controls.

However, in Credit Recovery Systems, LLC v. Hieke, the District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia struck down an agreement assigning the right to file Medicare and Medicaid claims for direct payment from the government. In that case, a clinic pledged its Medicare and Medicaid accounts as collateral and, when the clinic defaulted on the loan, the lender took possession of the assets and sold the accounts to Credit Recovery Systems.

The clinic later entered a settlement agreement with the government, whereby it agreed to abandon its rights to unpaid Medicare and Medicaid claims. Credit Recovery Systems filed an action seeking declaratory judgment that the assignment was valid, so it could file a claim with the government for the Medicare and Medicaid claims. The court held that the right to receive direct payments from the government cannot be assigned. This ruling effectively prevents a secured lender from exercising its remedies without a court order.

Conclusion

With certain precautions, a secured lender can include healthcare insurance receivables and accounts as collateral for a loan. In general, private healthcare insurance receivables are treated in the same manner as other accounts under the UCC. The process of collateralizing government healthcare accounts is more risky due to federal anti-assignment provisions. This risk can be mitigated with i.) a double lockbox arrangement with a daily sweep feature, ii.) a deposit account control agreement, iii.) a reduction of available credit, and/or iv.) exclusion of such receivables from the borrowing base.

Cheryl Camin is a shareholder in Winstead’s Healthcare Industry Group as well as the Corporate Securities/Mergers & Acquisitions Practice Group. Her practice focuses on healthcare matters, advising providers and businesses on entity formation and structural, contractual and regulatory healthcare issues. She can be reached by e-mail at: [email protected].

John Holman Jr. is a member of Winstead’s Finance & Banking Practice Group. He represents lenders and administrative agents in secured and unsecured debt financings and purchasers of debt. His transactions have included credit facilities for insurance holding companies, oil and gas companies, and commercial and residential construction and art-secured loans. He can be reached by e-mail at: [email protected].

Elaine Flores is an associate in Finance & Banking Practice Group. She can be reached by e-mail at: [email protected].

Disclaimer: Content contained within this article provides information on general legal issues and is not intended to provide advice on any specific legal matter or factual situation. This information is not intended to create, and receipt of it does not constitute, a lawyer-client relationship. Readers should not act upon this information without seeking professional counsel.