Managing Director,

Trimingham

Paul Warburg was an asset-based lending colossus who straddled the Atlantic Ocean between Europe and New York City for decades. The German-born American banker was a central figure in transatlantic asset-based financings in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

When he moved to New York City in 1902 to become a partner at Kuhn, Loeb on Wall Street, this transatlantic move elevated his firm, M.M. Warburg, into unrivaled prominence as an investment banking firm in Germany. “Even the House of Morgan was poorly informed about Europe in comparison to us,” boasted Max Warburg. In the late 1800s, Europe was the source of funding for many of America’s capital intensive industries such as railroads. The House of Warburg engineered a significant amount of the capital flow from Europe to America during this time. In Germany, the Warburg partnership was the distribution agent for secured term loans for American railroads underwritten by Kuhn, Loeb in New York for such issuers as Illinois Central and the Pennsylvania Railroad. Once he was in the U.S., Paul Warburg founded the American Acceptance Council, a pioneer in what we now consider discounted accounts receivable. He organized and became the first chairman of the International Acceptance Bank of New York in 1921 specializing in bills of exchange, which was acquired by the Bank of the Manhattan Company in 1929.

Reversing the tide of asset-based lending, ABL has migrated across the Atlantic from America to Europe in the past decade. According to Chris Hawes, corporate director, RBS Invoice Finance in London: “When Pan-European deals have been done, they have been structured out of the U.S., and the U.S. has been the majority of the borrowing base. We are some way off a true Pan-European syndicated loan market, but I see increasing willingness amongst UK and some European participants to work together towards this dream. I think that ABL, going beyond the A/R, is much more difficult to envisage in the short term on a Pan-European basis. The difficulties center around banking culture, jurisdictional ability to perfect security, borrower culture and regulatory and compliance matters. It’s a big challenge!”

An Important Tool

In years past, asset-based lending was considered transitional financing or a loan of last resort; today, borrowers are discovering the advantages of increased availability and become permanent ABL customers. Pan-European ABL deals have become an important tool in the toolbox of many CFOs of multi-jurisdictional companies in Europe.

Jonathan Parfitt, senior portfolio manager at ABN AMRO Commercial Finance comments, “Pan-European syndication loans can be delivered if European ABLs work together with their U.S. counterparts to create opportunities for large U.S. corporates to maximize funding of European assets. Other obstacles to overcome are minimizing workloads and simplification of operating finance facilities. There may not be sufficient multi-country ABL players, but there are enough in the Northern and Western European regions to collaborate and create effective syndication structures. Europe presents a great opportunity if lenders, with local expertise, work together to overcome the challenges in different legal jurisdictions to secure collateral. The challenge is to find the most cost-effective legal structures to maximize funding across an increased number of geographies and ultimately be more attractive to borrowers.”

Many asset-based lenders wonder: Are Pan-European syndicated loans a dream or close to reality? What are the obvious obstacles and hidden bear traps? Does the market have a sufficient number of multi-country ABL players to participate in a large facility? Does a bank need to be in all of the countries in order to agent the loan? Are Collateral Allocation Mechanisms a realistic way to deal with lenders who want to participate in Pan-European deals but can’t fund in certain jurisdictions? The Special Purpose Vehicle structure works as a CAM, but it is expensive and only cost effective for larger transactions. There are currently not many of these size ABL deals in Europe that justify an SPV. And the recentralization of assets has not been tested in bankruptcy court, giving pause to the credit committees of many asset-based lenders.

Two good recent examples of Pan-European/global ABL deals are: Ulster United Bank led a €300 million loan to Kingspan Group PLC across Europe, U.S. and Australia; and Barclays and Ulster Bank Ireland led a €135 million loan to Irish Dairy Board in Ireland, Europe and the U.S.

Alex Dell, partner at DLA Piper in London, comments, “As the emerging financial data suggests improved confidence in macro conditions, we have seen an uptick in ABL activity this year. Its application remains as varied as ever, it being used in secondary buyouts, bank-led syndicated working capital, strategic refinancing on softer covenants and pricing as well as defensive refinancing in response to a leveraged loan covenant breach. Added to that are the increasing instances of commodity/trade finance and asset- based combinations as well as off-balance-sheet structuring for investment grade credits. What is genuinely encouraging is the increasing understanding amongst the debt advisory and private equity communities who are learning more and more about the potential that ABL offers within a variety of contexts. A greater awareness of financing products in the market can only be a good thing for businesses as they consider their next move within the context of an increasingly positive outlook.”

Bi-lateral deals in different jurisdictions are much more difficult to do than Pan-European monolithic deals, and the complexity of differing jurisdictions

can be daunting. Due to the lack of harmony amongst many legal jurisdictions, lawyers and law play a much more prominent role in transactions than in the U.S. In many parts of Europe, lenders may need to audit the legal opinions of the borrowers’ legal counsel every bit as closely as the collateral. Some countries like Spain and Germany can have many qualifications in the borrower’s legal opinion — we heard of one instance in Spain where the legal opinion had 80 qualifications!

To syndicate a global deal, it needs to feel “American” to U.S. lenders. This means that financial statements must conform to GAAP and be in U.S. dollars.

“Globalization has shrunk the world, and successful asset-based lenders need to follow their customers as they expand beyond their home borders. It’s no easy task; however, advances in credit insurance processes and client receivables software have enabled the rise of the global asset-based lender,” comments Debbie Habib, business development director for FGI Finance’s European business.

UK Leaders

Asset-based lending in the UK is becoming more mainstream, as private equity and family owners see ABL as a way to maximize collateral. “Today, all eyes are on the UK as the country serves as a launching pad for U.S. lenders,” notes Habib. “Together, UK and U.S. asset-based lenders are setting the example for banks in Germany and the Netherlands who are actively working towards a true ABL platform.”

“If you look at consumer products markets in North America and Europe, there is a fair degree of stagnation, and thus many middle-market companies that were hitherto stridently domestic-focused are now thinking in terms of cross-border deals,” says Pierfrancesco Carbone, partner at Duane Morris in London. This opens up significant cross-border opportunities for asset-based lenders who work with private equity groups.

The UK has a tradition of being creditor friendly, so its emergence as a springboard for European asset-based lending is natural. The British rule of law is iron-clad and predictable, providing U.S. lenders with a sense of comfort in approaching a new marketplace.

Hawes in London notes, “ABL in the UK has become far more mainstream. We are seeing the UK Debt Advisory community proactively seeking to structure ABL facilities, and suggest these to their customers. At the same time, with many high-profile ABL deals having been done and publicized, we are seeing a greater acceptance in the borrower community. We’ve grown our ABL book from nothing to a £1 billion portfolio, and are still seeing good growth. However, the roll-over of cash-flow loans by existing lenders means ABL players are not winning as many transactions as anticipated.”

Partha Kar, partner at Kirkland & Ellis International LLP in London, adds, “Notwithstanding the availability of reasonably cheap bank financing for the last 18 months or so, we have seen an uptick of activity in asset-based lending, particularly amongst non-traditional lenders who believe they can offer flexibility and take more risks than the traditional lenders in some situations. The traditional UK clearing banks are tending to stick to vanilla UK deals, but non-bank funds (that are usually headquartered in the U.S.) have been prepared to do some tougher deals.”

Challenging deal structures can improve the yield on a loan; many better-yielding deals are a work-around, meaning a lender needs to be highly adaptive to the borrower’s geographic and legal condition. For plain vanilla deals, the pricing and terms have become so competitive that the internal hurdle rates of some asset-based lenders are not attainable.

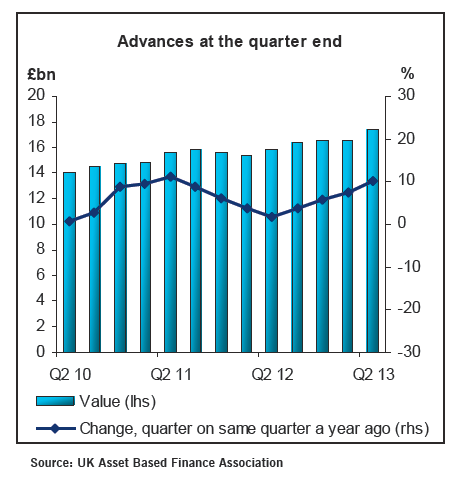

According to Kate Sharp, CEO of the UK Asset Based Finance Association, “There has been an uptick in ABL and factoring activity levels, covering refinancings, transactional and turnaround activity.”

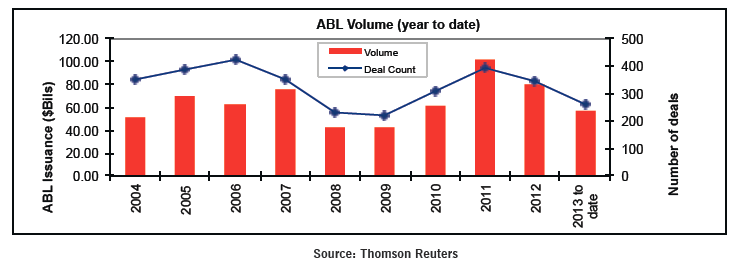

This is in contrast to the U.S., where asset-based lending has declined since peaking in 2011. According to Maria Dikeos at Thomson Reuters in New York, “It doesn’t feel that U.S. ABL volume should be as high as it is right now. There is so little M&A. You are not seeing large, transformative transactions.”

Dikeos adds, “As the market contracts, there has been pressure on pricing and spreads although discipline has not disappeared entirely.”

Many asset-based lenders have been surprised at the speed of the pendulum swing from risk-focus to marketshare-focus of many market participants. It seems that a new asset- based lender enters the marketplace weekly, and the new entrants often buy market share and cause market distortions.

In the aftermath of the credit crisis, many lenders swore off covenant lite deals and lending against pro forma EBITDA. But with the intense competition for good borrowers, these disciplines appear to have been pushed to the back burner.

Partha Kar notes, “Where asset-based lenders can get comfort on asset value and recoverability, we have seen deals become ‘covenant loose’ or even ‘covenant light,’ offering maximum flexibility to the borrower.” He sounds a note of caution: “An increase in the cross border and multi-jurisdictional nature of asset-based lending has meant lenders are very focused on enforcement and insolvency scenarios, and want to understand the risks and issues involved in recovering value from assets outside their home jurisdiction.”

Lenders know that private equity borrowers typically have stronger accounting and operational processes than privately held middle-market companies, so the risk profile is moderate. Pricing is intensely competitive on loans with private equity sponsors who have a reputation for standing behind their portfolio companies.

Carbone comments on ABL pricing for a typical private equity deal: “Drawn spreads are generally in the L + 175-200 bps area and remain below historical averages, although a larger share of transitional credits tapped the market in Q1/13 resulting in a 20 bps increase in average pricing. Unused fees typically range from 25 pps to 37.5 bps, with a step-up to 50 bps for larger deals or deals with little utilization. Lenders seem to be taking a long-term view of capital deployment and profitability as they prepare for the phase-in of Dodd-Frank and Basel III, explaining the relative stability in pricing and unused fees. Availability triggers for covenant testing and dominion range from 10% to 12.5%, and lenders are becoming increasingly flexible with respect to negative covenants. Absent a change in the macro backdrop, we expect the technical environment to remain favorable over the next several quarters given the light near-term maturity calendar and continued investor appetite to book assets.”

In the UK, Lloyds and RBS are ramping up their in-house private equity groups to domicile the equity from debt-to-equity conversions of middle-market companies. This represents new opportunity for asset-based lenders in 2014.

“Sorting out the capital structure for fundamentally decent businesses, most of whom will have some history that makes it difficult for conventional lenders to support, is a great opportunity for ABL. Now that the UK clearers are recapitalizing the walking wounded by converting debt to equity, will this lead to a faster healing for the marketplace? More opportunities for ABL players?” ponders Hawes.

The hedge funds and private equity players in Mayfair are providing good middle-market ABL deal flow. Cafe Nero is a good example. The UK’s third largest chain of coffee shops with more than 440 sites, Cafe Nero, had 2011 revenues of £171 million with EBITDA of £30 million. To refinance, the company deployed £90 million in senior secured debt, £99 million in mezzanine and preferred equity.

In another Mayfair transaction, Ideal Shopping Network, a leading home shopping retailer, went private with Inflexion Private Equity for a total deal of £70 million. Senior debt was £23 million or 33% of the total capitalization, mezzanine was 10 million of the total capitalization, with the balance in equity.

Other non-traditional financial players are active in the ABL space in Europe: The Ontario Teachers set up a team to do direct investments in Europe; and in London, HIG Whitehorse, GSO Blackstone, Fortress, Cerberus/Ableco and Blue Bay Asset Management have a wide range of targets across a diversity of asset classes.

“UK-headquartered private equity control deals in the £10 million to £100 million enterprise value range accounted for 45% of all UK buyouts completed in 2012,” according to Carbone. “This range includes a diverse pool of high-quality, small and medium-sized retail and consumer businesses. Over the past three years, secondary buyouts have outnumbered M&A transactions, and in 2012, they represented over 50% of the total number of exits. The UK and Ireland accounted for the largest proportion of M&A deals, with nearly 22% market share by deal value, followed by Germany (20%) and Central and Eastern Europe (18.5%).”

Given where we are in the cycle and with interest rates rates at a 300-year low in the UK, the moderate level of M&A activity has some market observers puzzled.

“Holding back private equity and asset-based lending activity is a lack of calibration between true enterprise value and what the seller is looking for in the way of price,” explains Philip Dougall, partner at middle-market buyout fund Kelso Place Asset Management in London. “Many middle-market companies have not been willing or able to fund capital programs at their companies — whether that’s new technology, processes or marketing spend. As a result, a lot of companies we see are a little bit ragged around the edges. But the seller doesn’t see it that way. We value our ABL partners, but we don’t expect them to stretch on collateral that is a little bit squishy.”

The growth in the UK ABL marketplace has also benefited from technology and gained the leading edge through better collateral transparency.

Habib comments, “The UK ABL industry has pioneered the development

of extraction software which allows lenders to extract account data on a real-time, ongoing basis and constantly oversee a client’s assets and other key account data. This technological innovation has made UK asset-based lenders the leading providers in Europe.”

Western Europe

Historically, asset-based lending has been centered on the “beer-drinking countries” — the UK, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands. ABL in the “wine-drinking countries” has been held back by challenging legal conditions. Financing for middle-market companies largely consists of demand and call loans with personal guarantees.

“Whilst market sentiment concerning European stability has eased, the ABL community, and other investors remain drawn to the core Northern and Western European markets. Aside from local partners, Southern European activity generally remains off market for most mainstream asset based lenders,” notes Sharp.

After the credit crisis, corporate borrowers started to geographically organize themselves based on liquidity considerations. In the past, borrowers often structured their company’s geographic and legal organization on tax considerations. There are some exciting trends in how companies with global operations are organizing their businesses in ways that facilitate the ability of lenders to provide financing involving multiple jurisdictions.

“Inadequate insolvency mechanisms have been one reason why asset-based lenders have not been more aggressive in expanding into the EU periphery,” according to Karl Clowry, partner at Paul Hastings (Europe) LLP in London. His London partner, James Cole, adds, “Recognizing that this structural impediment needs to be removed, numerous countries are rationalizing their insolvency procedures.” They also note “that the regulation of bank lending even in some key EU jurisdictions means we have to structure transactions funded by alternative debt providers as bonds or other locally compliant instruments. The treatment of lending as a regulated business in most European jurisdictions, together with tax and capital adequacy pressures, means that investors may require debt to be characterized as a bond rather than a loan.”

In transitional economies in the EU, term loans are difficult to obtain, and many working capital loan facilities are extended on a 30-day basis. The EU countries need harmonization of laws to encourage more stable forms of financing.

“Countries such as Slovenia have started the process of liberalizing their insolvency processes in order to expedite the insolvency and corporate revitalization process. Additionally, in Slovenia we have recently renewed our labor laws in order to give employers more leeway to restructure with the implementation of so called ‘flexicurity’ The privatization process, in order to be successful, will require this,” states Mojca Muha, partner at the law firm of Miro Senica in Ljubljana, Slovenia. “As part of the restructuring process, Slovenia has set up a bad bank — the Bank Asset Management Corporation, which scheduled to start in December 2013. Expunging the bad loans from a country’s banking system is the first step in priming the pump for new bank financing,” notes Marko Prusnik, attorney at law at Schoenherr in Ljubljana, Slovenia. “Additionally, Slovenia is privatizing 15 state-controlled companies, including well-known companies such Telecom Slovenij, Helios, Elan and Adria Airways.”

Adds Martin Ebner, partner at Scheonherr in Vienna: “Many transitional countries have recognized the importance of identifying and dealing with non-performing loans.”

For example, the Ukraine has set up a fund to buy bad loans from lenders. In Croatia, there are no bad banks as yet, but regulators are allowing lenders to transfer bad shipyard loans to the Croatian Ministry of Finance. Serbia has recently launched a privatization program for some of its banks in an effort to unclog the lending arteries.

With more than 6,500 banks in the eurozone, 70% of which are potentially insolvent according to S&P, the imminent transfer of bank supervisory powers to the European Central Bank couldn’t come at a better time. Industry observers hope that this will break the “doom loop” between sovereign governments and their banks, in which each invest in one another to create a Quixotic illusion of liquidity and solvency. The doom loop has kept investors on the sidelines up to this point. Investors are hoping that the ECB brings transparency and acid-washes to the portfolios of banks so that business can resume. The core EU banks suspect the EU periphery banks are hiding the scale of its bad debts. The periphery suspects the core. Everyone suspects the Italians, even the Italians, judging by recent public comments from a prominent Italian lender.

With a common currency, the troubled EU countries can’t use currency devaluation as a way out of their problems. An extreme example of devaluation in not so far off European history is post WWI Germany. In 1923, the enormous wartime debt of Germany was revalued, and bonds worth $36.7 billion at prewar exchange rates were reduced to a total of 15.4 pfennigs — less than four cents. If this wasn’t the largest haircut in history, it was surely the most spectacular. This legendary depreciation of the German currency reached its height in late 1923, when vast oceans of paper money drove hyperinflation. While none would advocate such a drastic measure of devaluation, a conservation trim could help the Southern Eurozone countries. Further, one of the key weaknesses of the EU is that common currency imperfectly calibrated with the banking system. Bankers in troubled countries would love to use currency devaluation as one way of dealing with their problems, but hands are tied with the euro.

Italy and The Isles

Like the junk bond market turning in the U.S. in 2009, U.S. high-yield investors are pumping new liquidity into the European banking system. Analogous to the impact on the U.S. asset-based lending marketplace, this will have a trickle-down effect on asset-based lending in Europe.

In their search for yield, hedge funds are piling into Greek bank debt, which in 2012 was like Ulysses sailing between the six-headed monster Scylla and the whirlpool Charybdis in Homer’s Odyssey. Confident that Greece is on the turn, John Paulson, Och-Ziff, Baupost, Eglevale, Falcon Edge, York Capital and Dromeus Capital are investing aggressively in Greek banks such as Alpha and Piraeus.

Italian banks are proving as tasty for investors as Tuscany’s pasta. In the past three months, Italian bank stocks are up 41%, despite the fact that two of Italy’s largest banks, Monte Paschi di Siena and Intesa Sanpaolo are troubled by bad loans. With the Italian political soap opera continuing unabated and the economy weak, bad loans increased 22.3% year over year in August. The banking sector’s ratio of non-performing loans to total lending has tripled to 14% since 2007, according to the IMF. The banking sector is burdened by an archaic bankruptcy regime in which it takes seven years on average to complete a bankruptcy; the snail-paced judicial system bars rapid write-offs of bad loans by the banks.

The ink was barely dry on the €65 billion IMF bailout of Ireland, and over 200 hedge funds were in the data room of the Irish Bank Rescue Corporation in October poring over a portfolio of troubled loans. Ireland has set up a bad bank, the National Asset Management Agency. “NAMA has already taken control of 12,000 real estate loans from the banks, valued at €74 billion, according to its 2012 Annual Report and Financial Statements,” notes Daragh Bohan, partner at Mason Hayes and Curran in Dublin. “Project Pittlane, a complex loan portfolio valued at €2.2 billion was sold to Apollo Global Management and CarVal Investors in September 2012 at a reported 75% to 90% discount.”

The Irish asset-based lending marketplace has seen the establishment of three new alternative asset-based funds: Blue Bay Capital’s Ireland-focused asset-based credit fund sponsored by The Royal Bank of Canada and the Irish pension system; Better Capital Ireland, which is a €100 million fund backed by the National Pensions Reserve Fund of Ireland; and a middle-market credit fund sponsored by The Carlyle Group.

All of these positive developments in liquidity and fresh capital should create opportunities for alternative lenders, well-capitalized banks and commercial finance companies, particularly those with strong, nimble ABL/invoice finance capabilities.

Growing Liquidity

All this to say that the rising tide of liquidity is lifting all boats. U.S.-style asset-based lending and a myriad of alternative credit facilities are spreading south from the UK as the regulatory environment evolves. Future harmonization of secured lending laws will eventually accelerate the growth of ABL in Europe.

The UK Asset Based Finance Association summarizes the state of asset-based lending in Europe: “As new business strategies start to evolve for major financial institutions in Europe, we are now starting to see an increasing divergence between those focusing on their domestic markets and others, either global relationship, or product institutions supporting their customers and product lines cross border into multiple jurisdictions. This includes the working capital and trade finance banks aligning around the trade flows of their customers and the product specialists whose relatively narrow product suite necessitates strategy evolving across regions and establishing ABL and factoring footprints across multiple markets.”

Paul Warburg brought to America an encyclopedic knowledge of asset-based lending and European central banking practices, and arrived on the eve of a historic debate over whether America needed a central bank. The nation hadn’t had a central bank since Andrew Jackson destroyed The Second Bank of the United States in 1836, and Paul Warburg’s detailed knowledge would be a valuable resource in the often ill-informed political debate. Many of his contemporaries regarded him as the chief driving force behind the Federal Reserve Bank.

Notably, on March 8, 1929, Warburg warned of the disaster threatened by the wild stock speculation then rampant in the U.S., foretelling the crash that occurred in October of that year. His legacy of financial acuity and innovation was continued in the early 1960s when Siegmund Warburg, his nephew, pioneered the Eurobond market, which would help rejuvenate London as a world financial center.

Hugh Larratt-Smith is a regular contributor to the ABF Journal. He is a managing director of Trimingham and is on the Advisory Board of The Commercial Finance Association Education Foundation in New York.